Fuzzing Like A Caveman 3: Trying to Somewhat Understand The Importance Code Coverage

Introduction

In this episode of ‘Fuzzing like a Caveman’, we’ll be continuing on our by noob for noobs fuzzing journey and trying to wrap our little baby fuzzing brains around the concept of code coverage and why its so important. As far as I know, code coverage is, at a high-level, the attempt made by fuzzers to track/increase how much of the target application’s code is reached by the fuzzer’s inputs. The idea being that the more code your fuzzer inputs reach, the greater the attack surface, the more comprehensive your testing is, and other big brain stuff that I don’t understand yet.

I’ve been working on my pwn skills, but taking short breaks for sanity to write some C and watch some @gamozolabs streams. @gamozolabs broke down the importance of code coverage during one of these streams, and I cannot for the life of me track down the clip, but I remembered it vaguely enough to set up some test cases just for my own testing to demonstrate why “dumb” fuzzers are so disadvantaged compared to code-coverage-guided fuzzers. Get ready for some (probably incorrect 🤣) 8th grade probability theory. By the end of this blog post, we should be able to at least understand, broadly, how state of the art fuzzers worked in 1990.

Our Fuzzer

We have this beautiful, error free, perfectly written, single-threaded jpeg mutation fuzzer that we’ve ported to C from our previous blog posts and tweaked a bit for the purposes of our experiments here.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

int crashes = 0;

struct ORIGINAL_FILE {

char * data;

size_t length;

};

struct ORIGINAL_FILE get_data(char* fuzz_target) {

FILE *fileptr;

char *clone_data;

long filelen;

// open file in binary read mode

// jump to end of file, get length

// reset pointer to beginning of file

fileptr = fopen(fuzz_target, "rb");

if (fileptr == NULL) {

printf("[!] Unable to open fuzz target, exiting...\n");

exit(1);

}

fseek(fileptr, 0, SEEK_END);

filelen = ftell(fileptr);

rewind(fileptr);

// cast malloc as char ptr

// ptr offset * sizeof char = data in .jpeg

clone_data = (char *)malloc(filelen * sizeof(char));

// get length for struct returned

size_t length = filelen * sizeof(char);

// read in the data

fread(clone_data, filelen, 1, fileptr);

fclose(fileptr);

struct ORIGINAL_FILE original_file;

original_file.data = clone_data;

original_file.length = length;

return original_file;

}

void create_new(struct ORIGINAL_FILE original_file, size_t mutations) {

//

//----------------MUTATE THE BITS-------------------------

//

int* picked_indexes = (int*)malloc(sizeof(int)*mutations);

for (int i = 0; i < (int)mutations; i++) {

picked_indexes[i] = rand() % original_file.length;

}

char * mutated_data = (char*)malloc(original_file.length);

memcpy(mutated_data, original_file.data, original_file.length);

for (int i = 0; i < (int)mutations; i++) {

char current = mutated_data[picked_indexes[i]];

// figure out what bit to flip in this 'decimal' byte

int rand_byte = rand() % 256;

mutated_data[picked_indexes[i]] = (char)rand_byte;

}

//

//---------WRITING THE MUTATED BITS TO NEW FILE-----------

//

FILE *fileptr;

fileptr = fopen("mutated.jpeg", "wb");

if (fileptr == NULL) {

printf("[!] Unable to open mutated.jpeg, exiting...\n");

exit(1);

}

// buffer to be written from,

// size in bytes of elements,

// how many elements,

// where to stream the output to :)

fwrite(mutated_data, 1, original_file.length, fileptr);

fclose(fileptr);

free(mutated_data);

free(picked_indexes);

}

void exif(int iteration) {

//fileptr = popen("exiv2 pr -v mutated.jpeg >/dev/null 2>&1", "r");

char* file = "vuln";

char* argv[3];

argv[0] = "vuln";

argv[1] = "mutated.jpeg";

argv[2] = NULL;

pid_t child_pid;

int child_status;

child_pid = fork();

if (child_pid == 0) {

// this means we're the child process

int fd = open("/dev/null", O_WRONLY);

// dup both stdout and stderr and send them to /dev/null

dup2(fd, 1);

dup2(fd, 2);

close(fd);

execvp(file, argv);

// shouldn't return, if it does, we have an error with the command

printf("[!] Unknown command for execvp, exiting...\n");

exit(1);

}

else {

// this is run by the parent process

do {

pid_t tpid = waitpid(child_pid, &child_status, WUNTRACED |

WCONTINUED);

if (tpid == -1) {

printf("[!] Waitpid failed!\n");

perror("waitpid");

}

if (WIFEXITED(child_status)) {

//printf("WIFEXITED: Exit Status: %d\n", WEXITSTATUS(child_status));

} else if (WIFSIGNALED(child_status)) {

crashes++;

int exit_status = WTERMSIG(child_status);

printf("\r[>] Crashes: %d", crashes);

fflush(stdout);

char command[50];

sprintf(command, "cp mutated.jpeg ccrashes/%d.%d", iteration,

exit_status);

system(command);

} else if (WIFSTOPPED(child_status)) {

printf("WIFSTOPPED: Exit Status: %d\n", WSTOPSIG(child_status));

} else if (WIFCONTINUED(child_status)) {

printf("WIFCONTINUED: Exit Status: Continued.\n");

}

} while (!WIFEXITED(child_status) && !WIFSIGNALED(child_status));

}

}

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

if (argc < 3) {

printf("Usage: ./cfuzz <valid jpeg> <num of fuzz iterations>\n");

printf("Usage: ./cfuzz Canon_40D.jpg 10000\n");

exit(1);

}

// get our random seed

srand((unsigned)time(NULL));

char* fuzz_target = argv[1];

struct ORIGINAL_FILE original_file = get_data(fuzz_target);

printf("[>] Size of file: %ld bytes.\n", original_file.length);

size_t mutations = (original_file.length - 4) * .02;

printf("[>] Flipping up to %ld bytes.\n", mutations);

int iterations = atoi(argv[2]);

printf("[>] Fuzzing for %d iterations...\n", iterations);

for (int i = 0; i < iterations; i++) {

create_new(original_file, mutations);

exif(i);

}

printf("\n[>] Fuzzing completed, exiting...\n");

return 0;

}

Not going to spend a lot of time on the fuzzer’s features (what features?) here, but some important things about the fuzzer code:

- it takes a file as input and copies the bytes from the file into a buffer

- it calculates the length of the buffer in bytes, and then mutates 2% of the bytes by randomly overwriting them with arbitrary bytes

- the function responsible for the mutation,

create_new, doesn’t keep track of what byte indexes were mutated so theoretically, the same index could be chosen for mutation multiple times, so really, the fuzzer mutates up to 2% of the bytes.

Small Detour, I Apologize

We only have one mutation method here to keep things super simple, in doing so, I actually learned something really useful that I hadn’t clearly thought out previously. In a previous post I wondered, embarrassingly, aloud and in print, how much different random bit flipping was from random byte overwriting (flipping?). Well, it turns out, they are super different. Let’s take a minute to see how.

Let’s say we’re mutating an array of bytes called bytes. We’re mutating index 5. bytes[5] == \x41 (65 in decimal) in the unmutated, pristine original file. If we only bit flip, we are super limited in how much we can mutate this byte. 65 is 01000001 in binary. Let’s just go through at see how much it changes from arbitrarily flipping one bit:

- Flipping first bit:

11000001= 193, - Flipping second bit:

00000001= 1, - Flipping third bit:

01100001= 97, - Flipping fourth bit:

01010001= 81, - Flipping fifth bit:

01001001= 73, - Flipping sixth bit:

01000101= 69, - Flipping seventh bit:

01000011= 67, and - Flipping eighth bit:

010000001= 64.

As you can see, we’re locked in to a severely limited amount of possibilities.

So for this program, I’ve opted to replace this mutation method with one that instead just substitutes a random byte instead of a bit within the byte.

Vulnerable Program

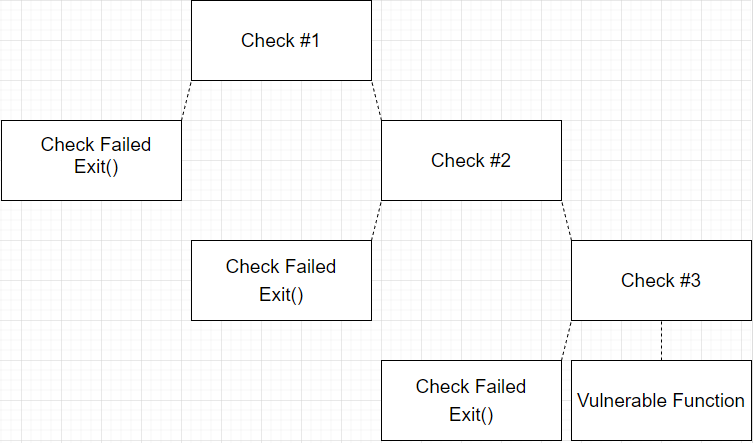

I wrote a simple cartoonish program to demonstrate how hard it can be for “dumb” fuzzers to find bugs. Imagine a target application that has several decision trees in the disassembly map view of the binary. The application performs 2-3 checks on the input to see if it meets certain criteria before passing the input to some sort of vulnerable function. Here is what I mean:

Our program does this exact thing, it retrieves the bytes of an input file and checks the bytes at an index 1/3rd of the file length, 1/2 of the file length, and 2/3 of the file length to see if the bytes in those positions match some hardcoded values (arbitrary). If all the checks are passed, the application copies the byte buffer into a small buffer causing a segfault to simulate a vulnerable function. Here is our program:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <errno.h>

struct ORIGINAL_FILE {

char * data;

size_t length;

};

struct ORIGINAL_FILE get_bytes(char* fileName) {

FILE *filePtr;

char* buffer;

long fileLen;

filePtr = fopen(fileName, "rb");

if (!filePtr) {

printf("[>] Unable to open %s\n", fileName);

exit(-1);

}

if (fseek(filePtr, 0, SEEK_END)) {

printf("[>] fseek() failed, wtf?\n");

exit(-1);

}

fileLen = ftell(filePtr);

if (fileLen == -1) {

printf("[>] ftell() failed, wtf?\n");

exit(-1);

}

errno = 0;

rewind(filePtr);

if (errno) {

printf("[>] rewind() failed, wtf?\n");

exit(-1);

}

long trueSize = fileLen * sizeof(char);

printf("[>] %s is %ld bytes.\n", fileName, trueSize);

buffer = (char *)malloc(fileLen * sizeof(char));

fread(buffer, fileLen, 1, filePtr);

fclose(filePtr);

struct ORIGINAL_FILE original_file;

original_file.data = buffer;

original_file.length = trueSize;

return original_file;

}

void check_one(char* buffer, int check) {

if (buffer[check] == '\x6c') {

return;

}

else {

printf("[>] Check 1 failed.\n");

exit(-1);

}

}

void check_two(char* buffer, int check) {

if (buffer[check] == '\x57') {

return;

}

else {

printf("[>] Check 2 failed.\n");

exit(-1);

}

}

void check_three(char* buffer, int check) {

if (buffer[check] == '\x21') {

return;

}

else {

printf("[>] Check 3 failed.\n");

exit(-1);

}

}

void vuln(char* buffer, size_t length) {

printf("[>] Passed all checks!\n");

char vulnBuff[20];

memcpy(vulnBuff, buffer, length);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

if (argc < 2 || argc > 2) {

printf("[>] Usage: vuln example.txt\n");

exit(-1);

}

char *filename = argv[1];

printf("[>] Analyzing file: %s.\n", filename);

struct ORIGINAL_FILE original_file = get_bytes(filename);

int checkNum1 = (int)(original_file.length * .33);

printf("[>] Check 1 no.: %d\n", checkNum1);

int checkNum2 = (int)(original_file.length * .5);

printf("[>] Check 2 no.: %d\n", checkNum2);

int checkNum3 = (int)(original_file.length * .67);

printf("[>] Check 3 no.: %d\n", checkNum3);

check_one(original_file.data, checkNum1);

check_two(original_file.data, checkNum2);

check_three(original_file.data, checkNum3);

vuln(original_file.data, original_file.length);

return 0;

}

Keep in mind that this is only one type of criteria, there are several different types of criteria that exist in binaries. I selected this one because the checks are so specific it can demonstrate, in an exaggerated way, how hard it can be to reach new code purely by randomness.

Our sample file, which we’ll mutate and feed to this vulnerable application is still the same file from the previous posts, the Canon_40D.jpg file with exif data.

h0mbre@pwn:~/fuzzing$ file Canon_40D.jpg

Canon_40D.jpg: JPEG image data, JFIF standard 1.01, resolution (DPI), density 72x72, segment length 16, Exif Standard: [TIFF image data, little-endian, direntries=11, manufacturer=Canon, model=Canon EOS 40D, orientation=upper-left, xresolution=166, yresolution=174, resolutionunit=2, software=GIMP 2.4.5, datetime=2008:07:31 10:38:11, GPS-Data], baseline, precision 8, 100x68, frames 3

h0mbre@pwn:~/fuzzing$ ls -lah Canon_40D.jpg

-rw-r--r-- 1 h0mbre h0mbre 7.8K May 25 06:21 Canon_40D.jpg

The file is 7958 bytes long. Let’s feed it to the vulnerable program and see what indexes are chosen for the checks:

h0mbre@pwn:~/fuzzing$ vuln Canon_40D.jpg

[>] Analyzing file: Canon_40D.jpg.

[>] Canon_40D.jpg is 7958 bytes.

[>] Check 1 no.: 2626

[>] Check 2 no.: 3979

[>] Check 3 no.: 5331

[>] Check 1 failed.

So we can see that indexes 2626, 3979, and 5331 were chosen for testing and that the file failed the first check as the byte at that position wasn’t \x6c.

Experiment 1: Passing Only One Check

Let’s take away checks two and three and see how our dumb fuzzer performs against the binary when we only have to pass one check.

I’ll comment out checks two and three:

check_one(original_file.data, checkNum1);

//check_two(original_file.data, checkNum2);

//check_three(original_file.data, checkNum3);

vuln(original_file.data, original_file.length);

And so now, we’ll take our unaltered jpeg, which naturally does not pass the first check, and have our fuzzer mutate it and send it to the vulnerable application hoping for crashes. Remember, that the fuzzer mutates up to 159 bytes of the 7958 bytes total each fuzzing iteration. If the fuzzer randomly inserts an \x6c into index 2626, we will pass the first check and execution will pass to the vulnerable function and cause a crash. Let’s run our dumb fuzzer 1 million times and see how many crashes we get.

h0mbre@pwn:~/fuzzing$ ./fuzzer Canon_40D.jpg 1000000

[>] Size of file: 7958 bytes.

[>] Flipping up to 159 bytes.

[>] Fuzzing for 1000000 iterations...

[>] Crashes: 88

[>] Fuzzing completed, exiting...

So out of 1 million iterations, we got 88 crashes. So on about %.0088 of our iterations, we met the criteria to pass check 1 and hit the vulnerable function. Let’s double check our crash to make sure there’s no error in any of our code (I fuzzed the vulnerable program with all checks enabled in QEMU mode (to simulate not having source code) with AFL for 14 hours and wasn’t able to crash the program so I hope there are no bugs that I don’t know about 😬).

h0mbre@pwn:~/fuzzing/ccrashes$ vuln 998636.11

[>] Analyzing file: 998636.11.

[>] 998636.11 is 7958 bytes.

[>] Check 1 no.: 2626

[>] Check 2 no.: 3979

[>] Check 3 no.: 5331

[>] Passed all checks!

Segmentation fault

So feeding the vulnerable program one of the crash inputs actually does crash it. Cool.

Disclaimer: Here is where some math comes in, and I’m not guaranteeing this math is correct. I even sought help from some really smart people like @Firzen14 and am still not 100% confident in my math lol. But! I did go ahead and simulate the systems involved here hundreds of millions of times and the results of the empirical data were super close to what the possibly broken math said it should be. So, if it’s not correct, its at least close enough to prove the points I’m trying to demonstrate.

Let’s try and figure out how likely it is that we pass the first check and get a crash. The first obstacle we need to pass is that we need index 2626 to be chosen for mutation. If it’s not mutated, we know that by default its not going to hold the value we need it to hold and we won’t pass the check. Since we’re selecting a byte to be mutated 159 times, and we have 7958 bytes to choose from, the odds of us mutating the byte at index 2626 is probably something close to 159/7958 which is 0.0199798944458407.

The second obstacle, is that we need it to hold exactly \x6c and the fuzzer has 255 byte values to choose from. So the chances of this byte, once selected for mutation, to be mutated to exactly \x6c is 1/255, which is 0.003921568627451.

So the chances of both of these things occurring should be close to 0.0199798944458407 * 0.003921568627451, (about .0078%), which if you multiply by 1 million, would have you at around 78 crashes. We were pretty close to that with 88. Given that we’re doing this randomly, there is going to be some variance.

So in conclusion for Experiment 1, we were able to reliably pass this one type of check and reach our vulnerable function with our dumb fuzzer. Let’s see how things change when add a second check.

Experiment 2: Passing Two Checks

Here is where the math becomes an even bigger problem; however, as I said previously, I ran a simulation of the events hundreds of millions of times and was pretty close to what I thought should be the math.

Having the byte value be correct is fairly straightforward I think and is always going to be 1/255, but having both indexes selected for mutation with only 159 choices available tripped me up. I ran a simulator to see how often it occurred that both indexes were selected for mutation and let it run for a while, after over 390 million iterations, it happened around 155,000 times total.

<snip>

Occurences: 155070 Iterations: 397356879

Occurences: 155080 Iterations: 397395052

Occurences: 155090 Iterations: 397422769

<snip>

155090/397422769 == .0003902393423261565. I would think the math is something close to (159/7958) * (158/7958), which would end up being .0003966855142551934. So you can see that they’re pretty close, given some random variance, they’re not too far off. This should be close enough to demonstrate the problem.

Now that we have to pass two checks, we can mathematically summarize the odds of this happening with our dumb fuzzer as follows:

((159/7958) * (1/255)) == odds to pass first check

odds to pass first check * (158/7958) == odds to pass first check and have second index targeted for mutation

odds to pass first check * ((158/7958) * (1/255)) == odds to have second index targeted for mutation and hold the correct value

((159/7958) * (1/255)) * ((158/7958) * (1/255)) == odds to pass both checks

((0.0199798944458407 * 0.003921568627451) * (0.0198542347323448 * 0.003921568627451)) == 6.100507716342904e-9

So the odds of us getting both indexes selected for mutation and having both indexes mutated to hold the needed value is around .000000006100507716342904, which is .0000006100507716342904%.

For one check enabled, we should’ve expected ONE crash every ~12,820 iterations.

For two checks enabled, we should expect ONE crash every ~163 million iterations.

This is quite the problem. Our fuzzer would need to run for a very long time to reach that many iterations on average. As written and performing in a VM, the fuzzer does roughly 1,600 iterations a second. It would take me about 28 hours to reach 163 million iterations. You can see how our chances of finding the bug decreased exponentionally with just one more check enabled. Imagine a third check being added!

How Code Coverage Tracking Can Help Us

If our fuzzer was able to track code coverage, we could turn this problem into something much more manageable.

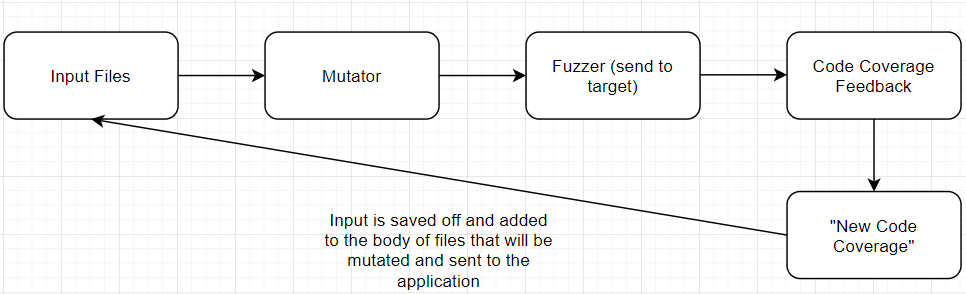

Generically, a code coverage tracking system in our fuzzer would keep track of what inputs reached new code in the application. There are many ways to do this. Sometimes when source code is available to you, you can recompile the binaries with instrumentation added that informs the fuzzer when new code is reached, there is emulation, etc. @gamozolabs has a really cool Windows userland code coverage system that leverages an extremely fast debugger that sets millions of breakpoints in a target binary and slowly removes breakpoints as they are reached called ‘mesos’. Once your fuzzer becomes aware that a mutated input reached new code, it would save that input off so that it can be re-used and mutated further to reach even more code. That is a very simple explanation, but hopefully it paints a clear picture.

I haven’t yet implemented a code coverage technique for the fuzzer, but we can easily simulate one. Let’s say our fuzzer was able, 1 out of ~13,000 times, to pass the first check and reach that second check in the program.

The first time the input reached this second check, it would be considered new code coverage. As a result, our now smart fuzzer would save that input off as it caused new code to be reached. This input would then be fed back through the mutator and hopefully reach the same new code again with the added possibility of reaching even more code.

Let’s demonstrate this. Let’s doctor our file Canon_40D.jpg such that the byte at the 2626 index is \x6c, and feed it through to our vulnerable application.

h0mbre@pwn:~/fuzzing$ vuln Canon_altered.jpg

[>] Analyzing file: Canon_altered.jpg.

[>] Canon_altered.jpg is 7958 bytes.

[>] Check 1 no.: 2626

[>] Check 2 no.: 3979

[>] Check 2 failed.

As you can see, we passed the first check and failed on the second check. Let’s use this Canon_altered.jpg file now as our base input that we use for mutation simulating the fact that we have code coverage tracking in our fuzzer and see how many crashes we get when there are only testing for two checks total.

h0mbre@pwn:~/fuzzing$ ./fuzzer Canon_altered.jpg 1000000

[>] Size of file: 7958 bytes.

[>] Flipping up to 159 bytes.

[>] Fuzzing for 1000000 iterations...

[>] Crashes: 86

[>] Fuzzing completed, exiting...

So by using the file that got us increased code coverage, ie it passed the first check, as a base file and sending it back through the mutator, we were able to pass the second check 86 times. We essentially took that exponentially hard problem we had earlier and turned it back into our original problem of only needing to pass one check. There are a bunch of other considerations that real fuzzers would have to take into account but I’m just trying to plainly demonstrate how it helps reduce the exponential problem into a more manageable one.

We reduced our ((0.0199798944458407 * 0.003921568627451) * (0.0198542347323448 * 0.003921568627451)) == 6.100507716342904e-9 problem to something closer to (0.0199798944458407 * 0.003921568627451), which is a huge win for us.

Some nuance here is that feeding the altered file back through the mutation process could do a few things. It could remutate the byte at index 2626 and then we wouldn’t even pass the first check. It could mutate the file so much (remember, it is already up to 2% different than a valid jpeg from the first round of mutation) that the vulnerable application flat out rejects the input and we waste fuzz cycles.

So there are a lot of other things to consider, but hopefully this plainly demonstrates how code-coverage helps fuzzers complete a more comprehensive test of a target binary.

Conclusion

There are a lot of resources out there on different code coverage techniques, definitely follow up and read more on the subject if it interests you. @carste1n has a great series where he goes through incrementally improves a fuzzer, you can catch the latest article here: https://carstein.github.io/2020/05/21/writing-simple-fuzzer-4.html

At some time in the future we can add some code coverage logic to our dumb fuzzer from this article and we can use the vulnerable program as a sort of benchmark to judge the effectiveness of a code coverage technique.

Some interesting notes, I fuzzed the vulnerable application with all three checks enabled with AFL for about 13 hours and wasn’t able to crash it! I’m not sure why it was so difficult. With only two checks enabled, AFL was able to find the crash very quickly. Maybe there was something wrong with my testing, I’m not quite sure.

Until next time!